Sports Investment Banking: How to Win the Super Bowl and the World Cup in the Same Year

No matter the economic climate, you can always bet on sports fans to show up for their favorite teams.

This partially explains why sports investment banking has become a hot field, with JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs launching their own sports coverage groups.

For a long time, sports teams and franchises were not worth that much, so banks rarely put their “A-Teams” on these deals.

But this started changing in the 2010s and early 2020s as team values skyrocketed and billionaires, sovereign wealth funds, and sports private equity firms all jumped into the sector.

We’ll do a full breakdown of the sector here, but as usual, we need to start with the definitions, trends, and drivers:

- What is Sports Investment Banking?

- Recruiting and Daily Life as an Analyst or Associate in Sports Investment Banking

- Sports Sector Trends and Drivers

- Sports Investment Banking by Vertical

- Sports Accounting, Valuation, and Financial Modeling

- Examples Valuations, Fairness Opinions, and Bank Presentations

- Sports Investment Banking League Tables: The Top Firms

- Exit Opportunities

- Where to Learn More

- Should You Take the Field in Sports Investment Banking?

What is Sports Investment Banking?

Sports Investment Banking Definition: In sports IB, bankers advise on equity and debt issuances, mergers, acquisitions, and restructuring deals for sports teams and leagues, sports-adjacent technology and services firms, and facilities such as arenas, stadiums, and racetracks.

I am using the same breakout that Inner Circle uses for its deals: Teams & Leagues, Technology & Services, and Facilities.

Like renewables, sports is a combination of other sectors:

- Teams & Leagues: This segment has the highest-profile deals that involve brand-name teams and big news stories (e.g., Sir Jim Ratcliffe and Manchester United or Mark Cuban and the Mavericks). This sector is the most different in terms of valuation and technical analysis because of nuances around licensing, player salaries, and different revenue streams.

- Technology & Services: This one includes any company that is built on top of sports, such as firms in the gambling, data/analytics, software, and live event sectors. These are mostly just TMT or tech companies with more exposure to sports. We also count gaming and esports firms

- Facilities: This includes stadiums, arenas, racetracks, and other performance venues. Deals could be done on a corporate level (i.e., the owners and operators of these facilities) or an individual asset level. It mixes public finance, project finance, real estate, and infrastructure.

As a result of these divisions, it’s difficult to “classify” sports IB teams.

Traditionally, teams in all these industry groups have covered sports, but we will probably see more dedicated coverage at the large banks.

Recruiting and Daily Life as an Analyst or Associate in Sports Investment Banking

Sports investment banking is not particularly specialized, so you don’t get extra points for having “industry experience” in the same way you might in an oil & gas, mining, or financial institutions group.

Also, it might be the only field where it’s 100x harder to get “industry experience” than to get into IB (good luck becoming an Olympic athlete or a professional footballer).

It does help to have industry experience in one of the related sectors (tech/TMT, real estate, infrastructure, public finance, etc.), and most people are better served by working in one of these first.

Beyond that experience, bankers look for the same qualities as always: High grades, a good university or business school, previous finance internships, and networking and interview prep.

Be prepared to discuss a recent sports deal (ideally involving a team or league) and have a rough idea of the trends, drivers, and valuation differences (see below).

If you win a job offer, your experience as an Analyst or Associate depends 100% on your vertical focus.

However, one common point across all the verticals is that IPOs are not common because there aren’t that many publicly traded sports teams, stadiums, or arenas.

SPAC IPOs for esports companies were “hot” for a short period in 2021, but they seem to have died off by now.

Therefore, expect more debt deals for stadiums and arenas and more M&A deals, spin-offs, divestitures, minority stake purchases, and JV deals for teams and leagues.

Traditional leveraged buyouts are also less common due to restrictions on ownership percentages and financing in many leagues.

You will probably get the most “balanced” experience in the technology & services vertical, but it will be similar to the standard TMT experience.

Sports Sector Trends and Drivers

Sports is unique because a mix of local, regulatory, and macro factors drives it:

- Audience Reception & Popularity – How popular is the sport? How many live viewers does the average game have? Is it suddenly popular among a certain demographic due to recent events or player relationships (e.g., Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce)? What are the viewing and attendance trends?

- Local Demographics – What’s the average household income in the stadium or team’s region? Is the population rising or falling? What about the “population per franchise” (PPF)? Are there enough fans to support multiple teams in the same city?

- Broader Economy – A healthier economy with more job creation and rising income levels tends to increase attendance and ticket/merchandise spending, but even in recessions and downturns, many sports teams are resilient because fans tend to have emotional connections that override logic.

- Potential for Revenue Growth – Can the team monetize more effectively via the sale of additional streaming/broadcast rights? What about VIP ticket sales, apparel licensing, and media partnerships? Teams are often bought and sold based on this future potential rather than today’s cash flows.

- Public / Private Split – This is vital for stadiums and arenas because it dictates where the funding will come from, but it also extends to other firm types. For example, a franchise could offload many facility-related expenses to its city if the local government owns the stadium. A lack of stadium control means less potential upside but also lower risk and expenses.

- Team Valuations – This may sound circular, but the fact that sports valuations have skyrocketed over the past few decades has created more deal activity. With teams valued at sky-high prices, deal participation is limited to institutional investors such as SWFs and PE firms (and the occasional billionaire). It’s much harder for a “casual fan” in the “high net worth but not a billionaire” category to participate.

- Regulations – Does the league allow private equity or other financial sponsor ownership? How many individuals can be team owners? Can they only purchase minority stakes, or is full control also allowed? Can teams carry debt? What about salary caps and contract lengths for players?

Sports Investment Banking by Vertical

It’s difficult to find “public companies” in these verticals because most teams, leagues, and stadiums are privately owned or owned via public/private partnerships.

Many leagues restrict ownership of teams to a certain number of people, which means that going public may not be an option.

This explains why Inner Circle has a separate “Limited Partnership Transactions” group.

All that said, we’ve attempted to find at least a few relevant companies and documents in each vertical:

Teams & Leagues

Representative Public Companies: Manchester United, Borussia Dortmund, Juventus FC, Madison Square Garden Sports (they own the New York Knicks and New York Rangers), Liberty Media Corporation, the Atlanta Braves, and Rogers Communications (owner of the Maple Leafs, Raptors, Toronto FC, and 20% of the Blue Jays).

A few smaller European football clubs also happen to be publicly traded (Ajax, Celtic, etc.).

The key metrics here include the number of games/events each season, the average attendance per game, the average ticket prices, the terms of broadcasting/streaming contracts, and the average player contract value and length.

Financial analysis comes down to fixed and variable revenue and expenses (i.e., to determine the team’s operating leverage).

For many teams, revenue streams such as streaming, broadcast, and other media rights are “relatively fixed” and have built-in escalations, such as $50 or $100 million yearly increases.

Therefore, most of the revenue analysis comes down to predictions for attendance, ticket prices, and merchandise spending.

Player wages tend to be the biggest expense, so teams such as Manchester United like to tout their shorter contracts to position themselves as being more “flexible”:

The tricky part is that while player wages could fluctuate a lot, they’re not exactly variable expenses; they’re more like “harder-to-predict expenses” because they change based on player trades, contract lengths, and salary caps.

There’s also some variation in how teams account for player wages, training, and equipment, with some capitalizing and amortizing this spending over time.

Fixed expenses include property maintenance, professional fees, advertising/marketing, security, catering, and general/administrative.

Technology & Services

Representative Public Companies: Flutter Entertainment (FanDuel and Betfair ), DraftKings, Madison Square Garden Sports (they also own esports teams), Tencent (they do everything), Catapult Group (sports analytics), Playtech, and Sportradar Group.

We are counting esports for video games, online gambling, and sports betting in this category.

Offline casino companies are not included because the dynamics are different: A big physical footprint means higher fixed expenses and dependence on in-person traffic, so they fall into the real estate investment banking category.

By contrast, many of these online betting and gaming companies are more like SaaS or consumer tech companies, with key drivers such as monthly active users, average revenue per user (ARPU), and even SaaS metrics like LTV and CAC.

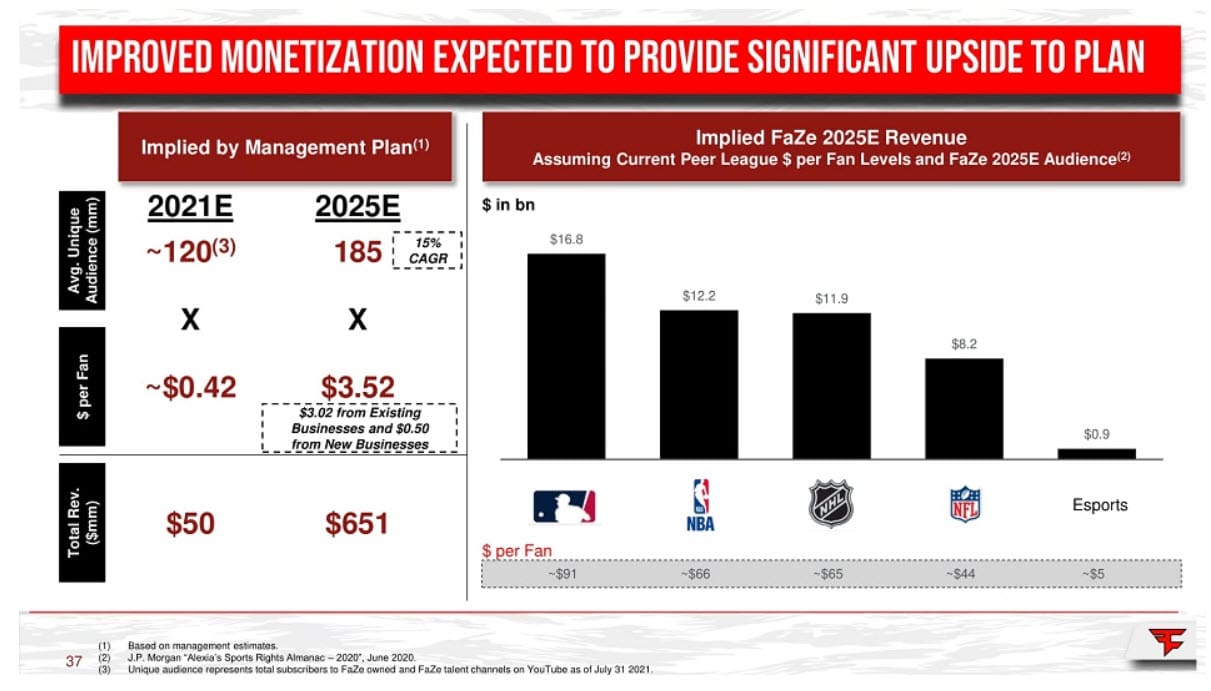

Companies such as FaZe in esports / gaming even welcome the comparison:

The analysis here is all about audience size, retention, per-user monetization, and margins in different scenarios.

Think TMT but with a football or baseball in your right hand and a mouse in your left.

Facilities (Stadiums, Arenas, etc.)

Representative Public Companies: N/A since these are almost always owned by cities, corporations, or specific teams.

Analysis of stadiums and arenas is the most specialized of anything here, but it’s also very close to what you do in public finance, real estate, or project finance.

This BofA presentation on the Raiders’ stadium in Clark County has many key points, as does this one for the Tennessee Titans’ stadium.

In short, the construction timeline and funding sources are critical for these projects.

Is it a mixed public/private project with some government contribution? Does the team contribute cash or any portion of its future revenue to fund the project?

If the local government is issuing new general obligation (GO) bonds to finance the project, what type of state/local tax is it implementing to support them?

Will there be an additional ticket or hotel occupancy tax to fund this?

For more on these points, please see the public finance investment banking article and the analytical examples there.

Once the stadium or arena becomes operational, it resembles more of a mature real estate project, such as a “core” property with a healthy net operating income (NOI) margin.

Here’s a good example for the Aloha Stadium redevelopment project, which has a very aggressive projected improvement:

Sports Accounting, Valuation, and Financial Modeling

We’ll focus on teams and leagues in this section because the other verticals are covered in the other industry group articles on the site.

My high-level summary would be:

1) Focus on Revenue Multiples – Many teams are not run efficiently and have low/negative cash flows and earnings, so revenue multiples are more common than EBITDA, P/E, or other valuation multiples. Also, different multiples may be applied to different revenue streams (see below).

2) Quirks Around Player Salaries, Payrolls, and Expense Recognition – Because player payrolls are a huge expense but also an inconsistent and highly variable one, you’ll sometimes see “EBITDA ex. Payroll” numbers used in valuations. Here’s an example from BofA’s analysis of the LA Clippers:

3) Royalty Relief and IP Valuation – To value a sports team’s intangible assets, you might use the “Royalty Relief” approach, which measures the theoretical cost of the team licensing their brand from a 3rd It requires assumptions for the revenue derived from the brand, the royalty rate, and the discount rate:

4) Sum-of-the-Parts Valuations and Blended Multiples – Since teams have revenue from varied sources, banks might value them based on the Sum-of-the-Parts approach and assign different multiples to each segment. They might also use “blended multiples” or “primary and secondary comps”:

5) “Emotional” Valuations – Finally, team valuations are often irrational because many deals involve individual billionaires as buyers or sellers. So, the price paid may be totally disconnected from the asset’s historical or projected cash flows. Yes, this also happens in other sectors, but it’s more prevalent in sports.

Examples Valuations, Fairness Opinions, and Bank Presentations

Finding these presentations and Fairness Opinions was quite difficult because most sports M&A deals involve non-public assets.

That said, I managed to locate a few examples in each category:

Teams & Leagues (and Related Holding Companies)

Los Angeles Clippers – Acquisition (BofA)

Silver Lake / Endeavor – Acquisition (Barclays, BofA, Centerview, DB, HSBC, JPM, MS, RBC, GS, Raine, and Wells Fargo)

- Deal Update and Valuation Summary (Centerview)

- WWE Fairness Opinions from the Year Before – Raine, MS, and Moelis (scroll to “Opinions of WWE’s Financial Advisors” on pg. 109)

- WWE and UFC Investor Presentation

Madison Square Garden Entertainment / MSG Networks – Acquisition (Moelis, Raine, JPM, PJT, GS, Guggenheim, LionTree, and MS)

- Investor Presentation

- Fairness Opinions – Moelis | LionTree

Liberty Media / Dorna Sports (Moto GP) – Acquisition (GS and Moelis)

Technology & Services

Courtside Group / PodcastOne – Restructuring and IPO (Roth Capital Partners)

Wanda Sports Group – U.S. Delisting and Acquisition by Wanda Sports & Media (DB)

HUYA / DouYu + Penguin E-Sports – Acquisition (GS, MS, and Citi)

- Deal Process Update and Valuation | Fairness Opinion (MS)

- Deal Process Update and Valuation | Fairness Opinion (Citi)

FaZe Clan – SPAC IPO (B. Riley, M. Klein, and Evolution Media Capital)

Stadiums and Arenas

Clark County Stadium Authority (Las Vegas Raiders) – Financing (BofA)

Tennessee Titans Stadium – Financing (GS, JPM, and several regional/boutique banks)

Aloha Stadium Redevelopment – Development Consortium

NASCAR / International Speedway – Acquisition (GS and DBO)

- Discussion Materials and Valuation (GS)

- Discussion Materials and Valuation (DBO) | Fairness Opinion (DBO)

- Global Economics Group – Offer Analysis

Sports Investment Banking League Tables: The Top Firms

Since sports IB is a rather new field, there are no real/consistent “league tables” yet.

Among the bulge brackets, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan should be at the top of this list now that they have dedicated teams (plus their existing reputations and market shares).

BofA is also strong, and you’ll see Citi, DB, and MS on many deals as well.

Outside the bulge brackets, many elite boutiques also advise on sports deals: PJT, Moelis, Evercore, and Rothschild (more so in Europe) are all examples.

LionTree and Allen & Co. are also on many sports deals, especially media-related ones.

Two of the best-known sports boutique banks are Inner Circle Sports and Galatioto Sports Partners; others include Park Lane, Game Plan LLC, and Grimes, McGovern & Associates (the last one is more active in the “events ” space).

Finally, Tifosy is a merchant bank that does a mix of sports advisory and lending/investing work.

Exit Opportunities

The good news is that no matter what you do, you probably won’t be pigeonholed because sports is a broad area without much specialized analysis.

Yes, sports private equity is one potential exit opportunity, but there aren’t that many dedicated firms, so I’m not sure how viable it is.

That said, you could go to plenty of TMT or technology PE firms or others that focus on real estate or infrastructure, depending on your experience.

Hedge funds are not especially viable because most sports teams and related assets are not publicly traded; the “play” here would be to aim for tech or TMT funds with some sports exposure.

Many bankers think about joining a sports team or league doing corporate development or business development work, which is possible (e.g., Madison Square Garden hires ex-bankers and consultants for these roles).

But beware that these roles have notoriously long hours with high stress and relatively poor pay – because “everyone” wants to work in sports finance.

It’s the same issue you run into when considering work in movies, TV, video games, or fashion: Since the industry is so desirable, they can afford to underpay and overwork you.

Where to Learn More

Some good resources for learning more about sports finance include:

- Sportico – The Business of Sports

- Sports Business Journal

- Front Office Sports

- Sports Pro News

- SportBusiness

- Forbes Sports Team Valuations – Updated each year with new estimates

- Houlihan Lokey – Indian Premier League (IPL) Valuation Study

Should You Take the Field in Sports Investment Banking?

Sports M&A and investing have become hot fields in recent years, but I’m not sure I would recommend joining the sports investment banking team for your first full-time role.

The problem is that sectors like this can quickly go from “hot” to “not” as macro conditions change, which means you might get poor or nonexistent deal experience.

The concept of institutionalized sports investing and deal-making is still new compared to other sectors, so you are taking a chance.

So, I would recommend joining a related coverage team (TMT, RE, PF, etc.) and gaining solid deal experience there first.

Once you have a hat trick of deals, you can think about stepping onto the field of sports investment banking.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews