SPAC vs IPO: Performance, Excel Model Differences, Trade-Offs, and Retail Investors

Now that the market has had a major correction and we’ve seen many SPAC deals play out, I wanted to look back and see if my views have changed.

I also want to make more of a proper SPAC vs IPO comparison from the perspective of both companies and investors.

The short answer is that SPACs can be reasonable alternatives to traditional IPOs for certain companies.

But for investors – especially retail investors – they’re still not a great deal unless you’re aiming for “quick flips” in which you buy the shares and sell them as soon as the price increases in response to a deal announcement.

SPAC performance since the peak of the market frenzy has been quite bad, but it’s not necessarily worse than all the other speculative assets since then.

I’ll get into all of that and clarify some points from last time, but let’s start with a quick recap and state of the SPAC market:

The SPAC Recap: How Did We Get Here?

If you want to watch or listen rather than read, you can access the video below:

Table of Contents:

- 3:09: Part 1: SPAC Recap and State of the Market

- 9:03: Part 2: SPAC vs IPO: Performance

- 12:42: Part 3: SPAC vs IPO in Excel

- 16:56: Part 4: SPACs for the (Retail) Investor

- 21:18: Part 5: What Happens Next in SPAC Land?

- 23:20: Recap and Summary

You can access the Excel file, presentation, and other links below:

- SPAC vs IPO – Presentation (PDF)

- SPAC vs IPO – Excel Models (XL)

- Pitch Book – Private Market Indices

- De-SPAC Screener

If you’re unfamiliar with SPACs, they allow private companies to go public via a 2-step process.

In the first step, a SPAC “Sponsor” forms an empty holding company, puts in minimal capital in exchange for 20% of the shares, and markets the SPAC to investors, usually at $10.00 per share:

In other words, the SPAC issues so many shares that the company ends up owning well over 50% of the entity:

If the deal is approved, the target company merges into the SPAC, the Balance Sheets are combined, and the company has effectively raised cash, just like it would in a normal IPO.

Other investors may also contribute capital in the form of a PIPE (private investment in public equity) at this stage:

- Speed – Companies can go public much faster than in the traditional IPO process (a few months rather than a year or more).

- Reduced Regulatory Burden – The SEC doesn’t have to approve the acquired company’s financials, disclosures, controls, etc., and the holding company that goes public is “empty,” so it receives no scrutiny at all.

- No Pricing Discount – Unlike in a normal IPO, the company doesn’t offer its shares at a discount to new investors. Instead, it negotiates with the SPAC for a price that both sides agree on.

But SPACs also come with disadvantages: they tend to result in greater dilution than IPOs, they’re not necessarily cheaper, investors often view these companies as lower quality, and their post-merger performance is “mixed” and often worse than IPO performance.

SPACs became the Shiny New Thing in 2020 and early 2021, but issuances have since fallen off a cliff:

They’ll never go away completely, but they’ve returned to their historical levels of a few dozen issuances per year rather than hundreds.

SPAC vs IPO: Performance Since 2018

In the original article, I predicted that most SPACs would perform poorly and leave investors worse off than traditional IPOs.

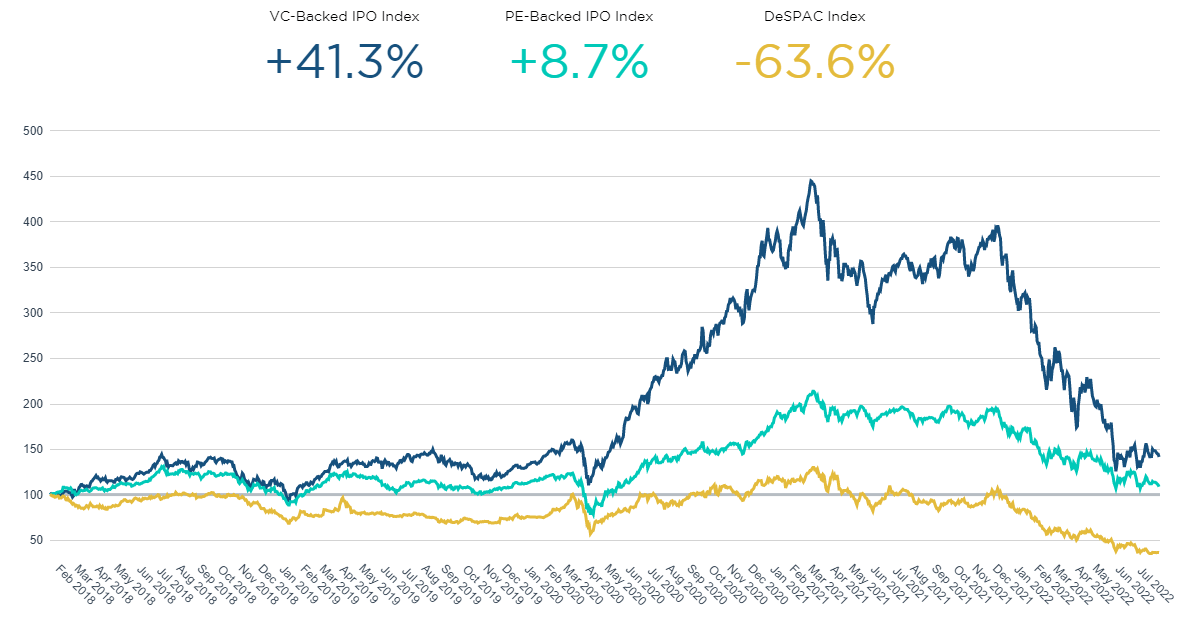

If we look at Pitch Book’s private company indices from 2018 to mid-2022, that appears to be the case:

Also, everything in tech/growth/speculative stocks is down by a huge amount in 2022.

If we go back only one year and look at performance from mid-2021 to mid-2022, De-SPAC deals have performed about the same as VC-backed IPOs (down almost 60%):

Of course, if you bought SPAC shares at $10.00 and sold them as soon as the price increased and before any deal closed (see below), you probably don’t care about any of this.

The bigger issue with SPAC performance is that there have been many high-profile failures, scams, and outright fraudulent behavior from companies: take a look at Nikola and ATI Physical Therapy for some examples.

Yes, some IPOs also turn out this way, but the frequency is far lower because of the extensive SEC review process before the company can sell its shares to the general public.

Outright fraud – at least for U.S.-based companies – is far less common.

This FT article sums up the results quite well: 1,000 SPACs have formed since 2020, more than 600 have not yet found an acquisition target, and there are 54 class-action lawsuits against SPACs (up to 64 now):

SPAC vs IPO in Excel and the Trade-Offs

For reference, you can get simple examples of IPO and SPAC deals in Excel and a direct comparison here.

The previous article overlooked an important point that a few readers pointed out in the comments: the IPO Pricing Discount.

Normally in an IPO, the company going public offers its shares at a modest discount (10-20%) to compensate investors for taking the risk of buying shares before the company is public.

This discount creates more dilution because it means that, for example, if the company is raising $200 million in capital:

- Normally, it might issue 20 million shares at $10.00 per share.

- But with a 20% discount, it would have to issue 25 million shares at $8.00 per share.

You can see this in the top part of the IPO model Excel file:

But in practice, it tends to make a small difference because this discount applies to only a small portion of the company’s shares – the ones it sells in the IPO.

In real life, the 20% Sponsor Promote in a SPAC deal almost always creates more dilution than a 10-20% discount on a small percentage of the company’s total shares outstanding.

So, a more proper SPAC vs IPO comparison looks like this:

But it’s unusual to offer a much higher Pricing Discount or to sell, say, 40-50% of the company.

People also like to claim that the fees are lower with SPACs, but this is not true.

The fees are distributed over more steps because there’s usually an upfront underwriting fee, a deferred underwriting fee, and fees on the M&A deal and the PIPE.

But the total fee percentage is still in the same range as most IPO fees, i.e., between 3% and 7% of the offering, scaling down to lower percentages for much larger deals.

Therefore, the main trade-offs are simple:

- SPACs: Companies get the speed and reduced regulation in exchange for greater dilution in the offering and possibly worse stock-price performance after the deal closes.

- IPOs: They take more time and are subject to greater regulatory scrutiny, but they tend to produce less dilution and possibly better stock-price performance.

SPACs for the Retail Investor

In the previous article, I focused on how the incentives were heavily skewed against retail investors in SPAC deals because of the 20% Sponsor Promote.

That Promote means that the SPAC’s share price can drop from $10.00 to $2.00 after the merger closes, and the Sponsor might still walk away with a profit – while the retail investors will be down 80%.

But there is a valid counterargument: “Who cares what happens after the merger closes? Just buy shares at $10.00, wait for the deal announcement to spike the share price, and sell your shares before the deal closes.”

The share price can certainly fall below $10.00 after the merger closes, but before that happens, $10.00 should be the floor – in theory.

So, your potential downside is 0% if you buy shares at $10.00 and sell before any deal closes.

It’s a bit like merger arbitrage: you’re accumulating small wins repeatedly over time with limited downside.

But there are a few problems with this idea.

First, a SPAC’s share price does not necessarily “pop” when a deal is announced.

Yes, there was a period from late 2020 to early 2021 in which this happened frequently, but it’s more of a mixed bag now.

Here are a few examples of names that did not experience “the pop”: SABS, ADSE, FATH, EMBK, BZFD, ADTH, DCGO, BTTX, KAL, and PGY.

For more ideas, look at the De-SPAC screen on Spactrack.io.

But the broader problem is that if the main strategy to make money from SPACs is the “quick flip,” then they’re not, in fact, comparable to traditional IPOs.

SPAC advocates kept going around during the peak and telling everyone they were viable alternatives to traditional IPOs.

That may be true in some sense for companies, but it’s a stretch to make this argument for retail investors.

Just admit that they’re speculative instruments intended for quick flips, not long-term investing, and this wouldn’t even be an issue.

What Happens Next in SPAC Land?

Earlier this year, the SEC made some noise about reforming SPACs, with proposals such as:

- Increased disclosures around SPAC Sponsors, their conflicts of interest, and the possible dilution investors might face after buying shares.

- The possible removal of “safe harbor” protections for financial projections of the acquired company in De-SPAC deals and liability under federal securities laws for Sponsors.

They want to make the SPAC process more similar to the IPO process and give investors the same transparency, including a possible Fairness Opinion to go along with any De-SPAC deal.

Skadden has a good summary of the potential changes here.

These ideas seem reasonable, but the SEC and other regulatory bodies are in a bit of a catch-22:

- If they make SPACs more like IPOs, they’ll also remove key advantages such as speed and the reduced regulatory burden.

- So, fewer high-quality companies will pick SPACs over IPOs.

- And SPACs will become riskier due to the (even) lower-quality companies, meaning the reforms ended up being a wash.

One alternative might be to require more disclosures or change how the Sponsor Promote works but keep the process and timing the same.

I don’t think speculative instruments like SPACs should be “banned.”

The issue is that they shouldn’t be marketed to new/gullible retail investors so that wealthy celebrities can profit from questionable deals.

The SPAC vs IPO Comparison: Final Thoughts

After looking at the data from the past 18 months, I’m less opposed to SPACs than I was last year – even though issuances have fallen off a cliff since then.

I still think the 20% Sponsor Promote in the initial deal is ridiculous and that it should be removed or linked to post-merger performance with some minimum hurdle rate.

But as others have pointed out, this Promote is mainly an issue if you buy SPAC shares and hold them until the merger closes.

SPACs can potentially be useful in certain situations, such as if a company needs to go public quickly for whatever reason.

But as governments crack down on this sector, some of these advantages may disappear.

Of course, that may not even matter if SPAC issuances remain at their current levels.

And we’ll probably need another pandemic, war, financial crisis, and massive stimulus before that changes.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews