Fixed Income Research: The Overlooked Younger Brother of Equity Research?

While everyone seems to know about equity research and trading stocks, fixed income research gets far less attention.

Partially, it’s an issue of accessibility: Everyone understands what happens to the stock price if a company beats earnings…

…but few people understand what it means if a company is set to violate a debt covenant on page 214 of its credit agreement.

But a few other reasons also explain why fixed income often gets overlooked: the unstructured recruiting process, fewer job openings, and the “cushiness” of senior-level roles.

For the right person, though, fixed income research can be even better than equity research, whether you’re at a bank, an asset management firm, a hedge fund, or a credit rating agency:

Table of Contents:

- What is Fixed Income Research?

- Equity Research vs. Fixed Income Research

- Common Myths

- What Do You Do as a Fixed Income Research Analyst or Associate?

- An Example Fixed Income Research Report

- Recruiting: Who Gets into Fixed Income Research?

- Interview Questions and Case Studies

- Salaries and Bonuses

- The Hours and Lifestyle

- Exit Opportunities

- Final Thoughts and Summary

What is Fixed Income Research?

Fixed Income Research Definition: In fixed income research, finance professionals analyze companies’ debt issuances and make pricing and investment recommendations based on their outlook for each one.

The confusing part is that fixed income research exists at banks (“sell-side roles”), buy-side firms such as asset managers and hedge funds, and even credit rating agencies, and each one differs.

Also, it can be quantitative or fundamental – or both! – and different teams specialize in different instruments (investment-grade, high-yield, distressed, structured, sovereign, emerging markets, etc. – see the fixed income trading article for the full list).

We can’t possibly cover them all in one article, so this one will focus on fundamental research at banks, primarily for investment-grade and high-yield bonds.

All the top investment banks and multi-manager hedge funds have fixed income research, and so do the top asset managers and credit firms: PIMCO, Brookfield (Oaktree), Fidelity, BlackRock, Wellington, Blackstone (GSO), Octagon, Ares, and so on.

And the credit rating agencies (S&P, Fitch, Moody’s, and Morningstar DBRS in distant 4th place) specialize in fixed income research.

Each role has common analytical elements, but the specifics and deliverables differ (e.g., a credit rating vs. an investment recommendation).

Equity Research vs. Fixed Income Research

The key difference in fixed income is that you focus on the downside case rather than growth:

- What are the chances the company will violate one of its covenants?

- Could the company default on one of its issuances?

- What if there’s a recession or a slowdown in global trade?

- If the company liquidates, which lenders will get their money back?

The fixed income market dwarfs equities in terms of market value and trading volume, but that does not necessarily translate into “more jobs.”

Liquidity is also more limited, and more trading is still done over the counter (OTC) rather than electronically.

And there is sometimes less turnover because senior staff tend to stick around longer.

Common Myths About Fixed Income Research

Some people claim that there’s more of a “macro focus” in fixed income research or that it’s more “quantitative” than equity research (i.e., closer to the work at a quant fund).

The problem is that these claims only apply to certain groups.

For example, if you focus on investment-grade bonds, you will focus more on macro factors because investment-grade companies rarely default.

Therefore, movements in interest rates drive bond prices more than other factors.

And if you’re in a “quant credit” group or something similar, sure, you could use statistics to analyze bonds rather than traditional 3-statement and cash flow modeling.

However, many fundamental roles within FI research still relate to the financial statements, debt analysis, and company-specific factors.

What Do You Do as a Fixed Income Research Analyst or Associate?

As in equity research, “Analyst” is the senior role, and “Associate” is the entry-level position.

Confusingly, there are also different “levels” within these, such as VP-level and MD-level Analysts.

Many of the work tasks are quite similar:

- You normally get assigned 1-2 industries and cover a specific set of companies; you’ll create or update a 3-statement model with support for credit features for each company.

- You split your time between new bond issuances and existing ones, similar to “initiating coverage” vs. “existing coverage” in ER.

- You cover quarterly earnings and send updated models and notes to clients and other teams.

The differences vs. equity research lie in the details:

- Financial models focus on the downside scenarios and analyze each issuance separately: the Yield to Worst, Yield to Maturity, Recovery percentages, and the default risk.

- The output is more about the credit stats and ratios (Debt / EBITDA, EBITDA / Interest, etc.), the appropriate debt vs. equity mix, and additional capital needs over the next few quarters.

- You may have to cover dozens of issuances, meaning you cannot spend that much time on a single company or bond.

- The legal side is quite important because you must read the debt agreements to understand each issuance’s covenants and other terms.

- Quarterly earnings calls and management interaction are a bit less important because it’s not always practical to participate when you cover 50 companies; also, events outside of earnings calls can sometimes be more meaningful for bond prices.

An Example Fixed Income Research Report

You can find fixed income reports on sites like Moody’s, Fitch, and S&P, but these tend to focus on the credit rating process instead.

So, I’ll share here an old report issued by Goldman Sachs on J.C. Penney.

Due to the age and the fact that J.C. Penney later declared bankruptcy, I don’t think this is particularly sensitive (but I may still remove it if it becomes an issue).

You can see that the “investment recommendation” is quite different:

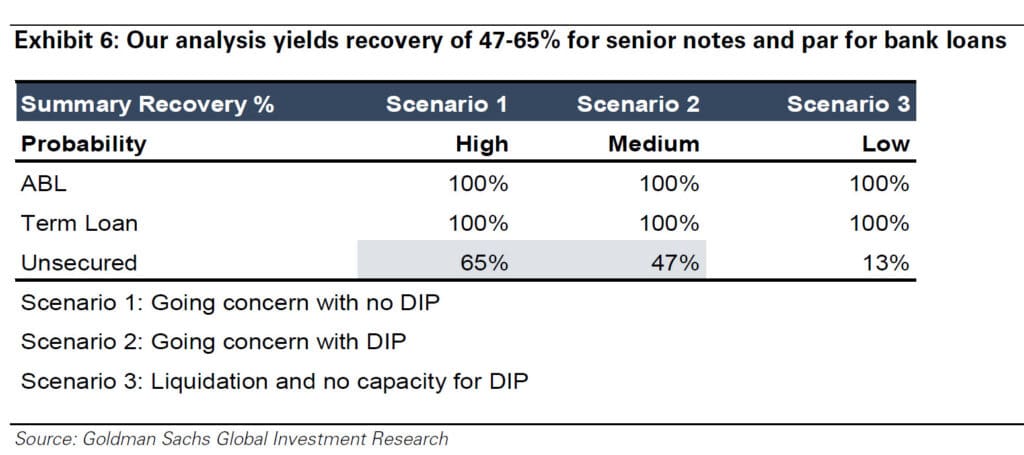

The model includes different scenarios, but they’re not the typical Bear / Neutral / Bull cases used in equity research.

Instead, the scenarios are based on the company’s prospects: Liquidation vs. going concern vs. debtor-in-possession financing (see the restructuring IB article for more about these):

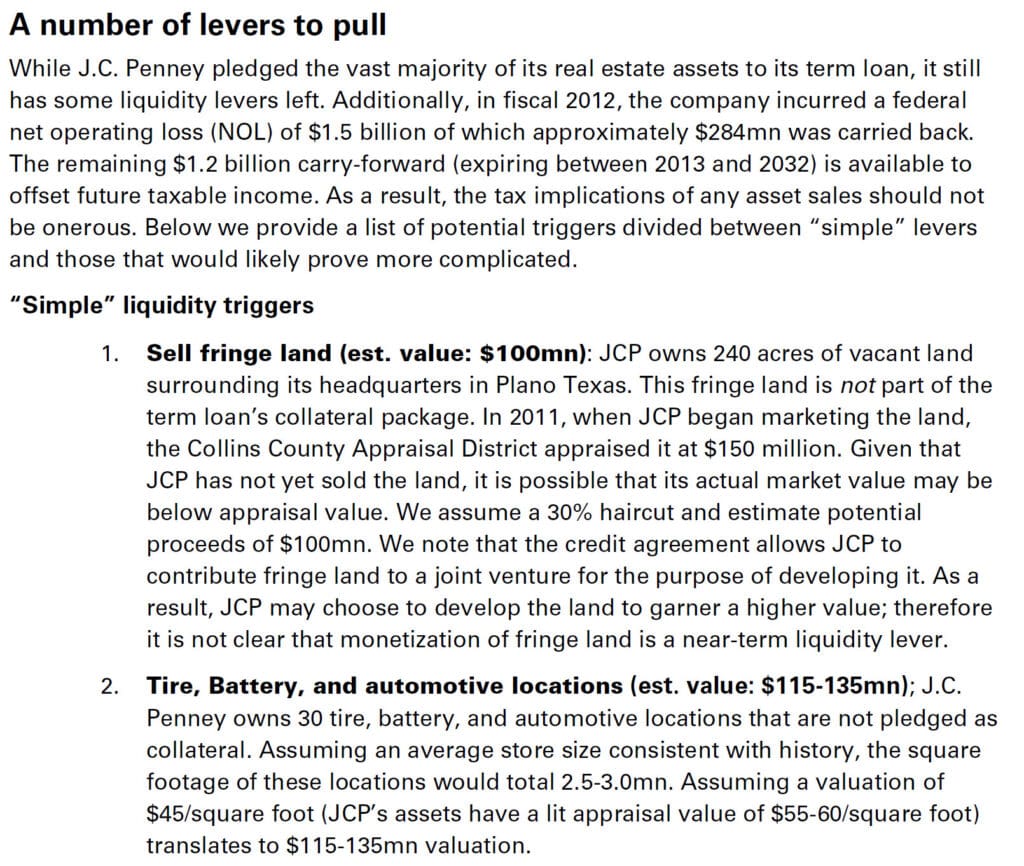

Throughout the report, there’s also a discussion of liquidity triggers rather than traditional catalysts – because they’re concerned about how events will affect the company’s ability to repay or refinance its debt:

Recruiting: Who Gets into Fixed Income Research?

As with equity research and hedge fund roles, there are two main options for breaking in:

- Complete the CFA, get fixed income-related internships, and start working directly in FI research, either at a bank or a buy-side firm.

- Do something else in finance first, such as corporate banking, capital markets, or a credit rating agency role (any job with the “Credit Analyst” title works). Sometimes, fixed income traders even get in (depending on their desk and role).

The hiring process is random and unstructured with no real “cycles” (unlike recruiting for IB and PE roles).

Some of the biggest asset managers, such as BlackRock and Fidelity, offer internships and entry-level roles in fixed income research, but they are incredibly competitive to win.

Banks do not appear to offer many internships in this area, so if your goal is a bulge bracket bank, you’ll likely have to work in other credit roles first and network your way in.

Fixed Income Interview Questions and Case Studies

To get an idea of interview questions, please review the articles on corporate banking, credit hedge funds, and distressed debt hedge funds because the topics covered are similar.

A few examples:

- Markets: What’s the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield at? What about gilts (U.K.), bunds (Germany), or Japanese government bonds (JGBs)?

- Bond Prices and Yields: What’s the difference between the Yield to Maturity, Yield to Call, and Yield to Worst, and how do you use them in real life? What might cause a bond’s price to change?

- Bond Math: How can you approximate the Yield to Maturity? What about the duration and convexity? What does duration mean intuitively?

- Rates: Is the “risk-free rate” truly risk-free? If so, how could you still lose money by investing in a 10-year government bond in a “safe” country?

- Rate Changes: If interest rates are set to rise over the next year, how would you structure your portfolio? Would investment-grade or high-yield bonds show more of an impact?

- Bond Types: How are corporate bonds different from government bonds? How would you analyze them differently?

If you get a case study, the most likely task will be to read 2-3 pages about a company and its bond issuances and make an investment recommendation on a specific issuance.

If it’s a high-yield or distressed bond, they could also ask you for a specific price target or a recommendation with credit default swaps (CDS) included, as in the report above.

Since the default probability is so low for investment-grade bonds, much of it comes down to macro factors, relative value, and portfolio “fit.”

For example, maybe a company has a 5% bond due in 10 years and a 6% bond due in 1 year.

Neither one is likely to default, but the 6% bond doesn’t necessarily “win” because:

- If you believe interest rates are set to drop substantially, you could earn a higher yield if you buy the 5% bond, wait for the rate drop, and sell it before maturity because it’s more sensitive to interest rates.

- The 1-year maturity for the 6% bond is quite short, and it may not match your overall portfolio’s duration target.

You must also consider these issuances vs. those of similar companies: Is 5% or 6% a good deal? Can you find lower/higher yields in the market?

The top mistake in these case studies is not picking a specific issuance to invest in, especially if the company has a wide range of bonds with different maturities.

Fixed Income Research Salaries and Bonuses

There isn’t much information about salaries and bonuses, but for sell-side roles, you should expect a discount to equity research compensation.

If ER Associates initially earn $150 – $200K for total compensation, FI Associates might start in the $100 – $150K range.

In equity research, some MD-level “Analysts” could potentially earn $1 million+ from their base + bonus, but the pay ceiling is lower in most fixed income roles.

Expect something more in the “mid-six-figures” range (though there are exceptions for top-performing groups and Analysts).

In buy-side fixed income research roles, Analysts can earn $300K+ depending on the firm and their seniority, and the PMs above them can earn a multiple of that (again, depending on the firm type and performance).

The Hours and Lifestyle in Fixed Income

The good news is that the hours in fixed income research are generally better than equity research because there’s less of a need to follow earnings calls closely or issue new reports constantly.

Since you cover so many more names, it’s more about forming an overall view of the market and your coverage universe.

So, expect something closer to a “normal” workweek, such as 50 – 55 hours, spiking a bit when a major event occurs.

And at buy-side firms such as asset managers, plenty of fixed income research professionals work 40 – 50 hours per week and have relatively low stress levels.

Fixed Income Research Exit Opportunities

Most people in research want to work at hedge funds, so let’s start there.

Hedge funds are more plausible if you focus on high-yield or distressed issuances because few HFs invest in investment-grade bonds, and the skill sets differ.

However, you’ll also be up against bankers who worked in groups like Leveraged Finance and Restructuring, so hedge funds are not necessarily a “sure thing.”

Traders have a big advantage when recruiting for global macro hedge funds, but you don’t have quite the same advantage when applying to credit-focused HFs.

You could also move into equity research or investment banking, especially if you focus on groups where credit is extremely important (e.g., power & utilities, FIG, or industrials).

Distressed private equity is theoretically possible if you find a firm that operates more like a hedge fund, but it’s not especially likely.

The most likely outcome is that you’ll continue working in credit-related research roles at a bank or an asset manager.

Exits like traditional private equity, corporate development, and venture capital are unlikely because you need deal experience.

Final Thoughts: Is Fixed Income Research Worth It?

Summing up everything above, here’s how you can think about fixed income research:

Pros:

- The work is arguably more interesting than equity research, at least if you cover high-yield or distressed issuances.

- It can be a nice “second step” after a role like corporate banking, capital markets, or a credit rating agency if you want to improve your profile for buy-side roles.

- It is very cushy at the top, as senior-level staff can earn into the mid-six-figures (or higher) with less stress than IB/PE-style jobs.

- You can move around to plenty of other credit-related roles.

Cons:

- There’s little turnover, which means that recruiting has a very high “luck” component.

- Exit opportunities exist, but they’re narrower than IB/PE exits because you do not work on deals.

- The work can get repetitive, especially if you focus on investment-grade issuances.

- Compensation is often a discount to equity research and “equities in general” (but there’s lots of variance for different firm/fund types, performance, etc.).

It is a shame that fixed income research gets overlooked, but it’s also understandable.

That doesn’t make it a bad area to get into – but if you do, be prepared to stay there for a long time as you grind your way up.

Hopefully, that Senior Analyst above you will retire one day.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Hey Brian I wanna know if Fixed Income is better than Equities (Active FI & E) for someone who wants to get in a Absolute Return Fund like those offered by top Asset Management firms, PIMCO, BlackRock, Fidelity, JPAM, etc. like if the asset class specialization matters for becoming a PM of such a fund, or will I have to think something else i.e Multi Asset:(

Great question. Unfortunately, I don’t know the answer to this one. Most absolute return funds are diversified, so I imagine that either FI or Equities could work. Equities might be slightly better overall just because these portfolios probably have a higher % allocated to equities than other assets, but I’m really not sure about this one.

Brian – the idea of a *career* in finance makes me queasy, however the idea of periodically pillaging markets during boom/bust situations a la George Soros is very appealing.

Call options on Tesla and GameStop during the squeezes, puts on blackberry when the iPhone comes out, snatching up zero coupon bonds before the fed lowers rates when Covid happens and then selling them and going long the cloud, etc

Do you think this is a viable strategy? If so, would you use anything more exotic then basic calls and puts for limited downside with unlimited upside?

I feel like super specialized skills are not necessary and perhaps even harmful for this kind of strategy. You don’t need aadvanced accounting like the pure play value guys, and you don’t need stochastic finance like the quants. Just the basics of everything molded into a lattice work of mental models per Charlie Munger.

What do you think of this?

I don’t know what your actual question is, so I’m not sure what to say.

If your question is “Can I take some of my money and bet on companies/markets and earn something from that?” then the answer is “Sure, but don’t expect to become wealthy quickly or at all because it’s much harder than you think to do this and be consistently profitable.” It’s easy to point to some of the examples you’ve listed and think about how well you could have done, but hindsight is 20/20, and traders make plenty of losing bets as well.

Yes, there are ways to reduce the downside risk in these trades, but I still would not recommend “casual trading” for most people unless it’s a small percentage of your total assets. It is extremely difficult to follow and successfully bet on individual companies, deals, etc. unless it is your full-time job.