Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance: Careers, Recruiting, Financial Modeling, and More

- Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance: The Video and Files

- What is Project Finance?

- Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance: Careers

- Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance: Recruiting

- Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance: Financial Modeling

- Wait, How Does Project Finance Math Work?

- Project Finance vs Corporate Finance: Final Thoughts

- Want more?

With the craze over renewable energy and infrastructure over the past few years, we’ve received more and more questions about Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance.

This article will focus on careers and recruiting, while the accompanying YouTube video will discuss the technical/modeling aspects in more detail.

And yes, coincidentally, we have a new Project Finance & Infrastructure Modeling course.

This article is a sample/excerpt/preview from the full course:

Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance: The Video and Files

You can get the presentation, the simple Excel file, and the video version of this article below:

Video Table of Contents:

- 0:00: Introduction

- 1:22: Part 1: The 2-Minute Summary

- 3:47: Part 2: Assets and Legal Structures

- 4:59: Part 3: Time Frame and Model Structure

- 6:17: Part 4: Debt Usage and Terminal Value

- 9:25: Part 5: How the “Deal Math” Works

- 12:21: Recap and Summary

What is Project Finance?

Project Finance Definition: “Project Finance” refers to acquisitions, debt/equity financings, and new developments of capital-intensive infrastructure assets that provide essential utilities and services.

Sectors within infrastructure include utilities (gas, electric, and water distribution), transportation (airports, roads, bridges, rail, etc.), social infrastructure (hospitals, schools, etc.), energy (power plants and pipelines), and natural resources (mining and oil & gas).

Many of these assets last for decades, have stable/predictable cash flows, use substantial Debt (50 – 60%+ of the total price), and use sized and sculpted Debt.

The term “Project Finance” at large banks refers to a group that operates like Debt Capital Markets or Leveraged Finance but for infrastructure rather than normal companies.

However, many people also use the term more broadly to refer to equity, debt, and advisory for infrastructure assets.

Like groups such as Leveraged Finance, DCM, and Direct Lending, the bulk of the analytical work involves assessing the downside risk.

In other words, if you lend $500 million to fund a new offshore wind development, what are your chances of losing money?

What if there’s a budget overrun or construction delay? What if market rates for electricity fall?

You’ll assess these questions and then indicate the terms you’d be comfortable with, from the Interest Rate to the Tenor (loan life) to the covenants (e.g., requirements such as maintaining a minimum Debt Service Coverage Ratio of 1.50x or 2.00x).

Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance: Careers

From a career perspective, “corporate finance” roles are generalist and exist at normal companies, investment banks, and many investment firms.

“Corporate finance” is a broad term that could refer to anything from managing a company’s internal budget (e.g., in FP&A roles) to advising clients on M&A deals in investment banking.

The unifying factor is that you work at the company level in corporate finance.

Even if you’re budgeting for a specific division or creating forecasts for one segment, your work affects the entire company.

By contrast, Project Finance roles are more specialized and “siloed.”

You analyze specific assets that operate independently, and if something goes wrong with one asset, the lenders only have a claim on that asset and its debt due to the special purpose vehicle (SPV) created for each asset.

You may still consider the entire portfolio when making decisions, but there’s less of a direct connection than in corporate finance roles.

One way to think about these roles is this analogy (if we limit “corporate finance” to just deal-based roles such as investment banking and private equity):

Infrastructure Investing : Project Finance :: Private Equity : Large Bank Lenders

If you view it this way, the comparison is as follows:

- Pay tends to be lower in PF/Infra roles because the targeted returns are lower, the upside is more limited, and many funds are smaller than traditional PE firms. Expect a ~20-30% discount to compensation in traditional IB/PE roles.

- The hours in PF/Infra are better because there’s less “hustle culture,” deals are sometimes simpler to evaluate, and senior bankers are less likely to abuse junior staff.

- The skill set in PF/Infra is more specialized because modeling Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) for a solar plant doesn’t translate that well into valuing a consumer/retail company.

- Stability is higher in PF/Infra roles because the underlying assets are essential, and the holding periods are very long.

- The exit opportunities in PF/Infra roles are more specialized, and moving to a generalist role would be difficult after significant time in the field. Credit, lending, and corporate development roles at client companies are possible.

Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance: Recruiting

We’ve covered investment banking recruiting, private equity recruiting, and even “corporate finance at normal company” recruiting many times on this site, so I’ll refer you to those articles.

The big difference in Project Finance is that they strongly prefer candidates with credit experience in LevFin, DCM, mezzanine, direct lending, and related fields.

You can win PF roles right out of undergrad, but recruiting for undergrads and recent graduates is less common and structured than in fields like investment banking, corporate banking, or wealth management.

And if you do this, you’ll probably need highly relevant internships, such as ones in credit, energy, renewables, or other infrastructure-related fields.

Interviews are more specialized, and you can expect everything from infrastructure modeling tests and case studies to questions about the deal execution process.

Because most of these assets are private, finding substantial information for deal discussions can be very difficult.

Therefore, you’ll probably have to focus on high-profile assets that operate more like normal companies, such as large airports – or research funds or large companies in the sector.

You should also expect technical questions about concepts unique to Project Finance, such as Debt sizing/sculpting based on future cash flows and how to use Goal Seek and VBA to resolve circular references in models.

See the sample Excel file included here for very simple examples of this.

We don’t have space in this article to cover technical questions, but we may publish a separate feature on this topic.

Project Finance vs. Corporate Finance: Financial Modeling

Here’s a chart summarizing the key modeling and analytical differences:

Types of Assets and Legal Structure

The “Types of Assets” category should be obvious if you’ve made it this far in the article.

The Legal Structure category is important because the special purpose vehicle around an infrastructure asset reduces the risk for the owner.

The Debt is also non-recourse, which means the lenders can seize only the collateral if something goes wrong.

So, the asset is “isolated” from the rest of the company, and the lenders cannot seize other assets if something goes wrong with the one specific asset they’ve funded.

Lenders see this feature not as “risk reduction” but “risk reallocation” – to them.

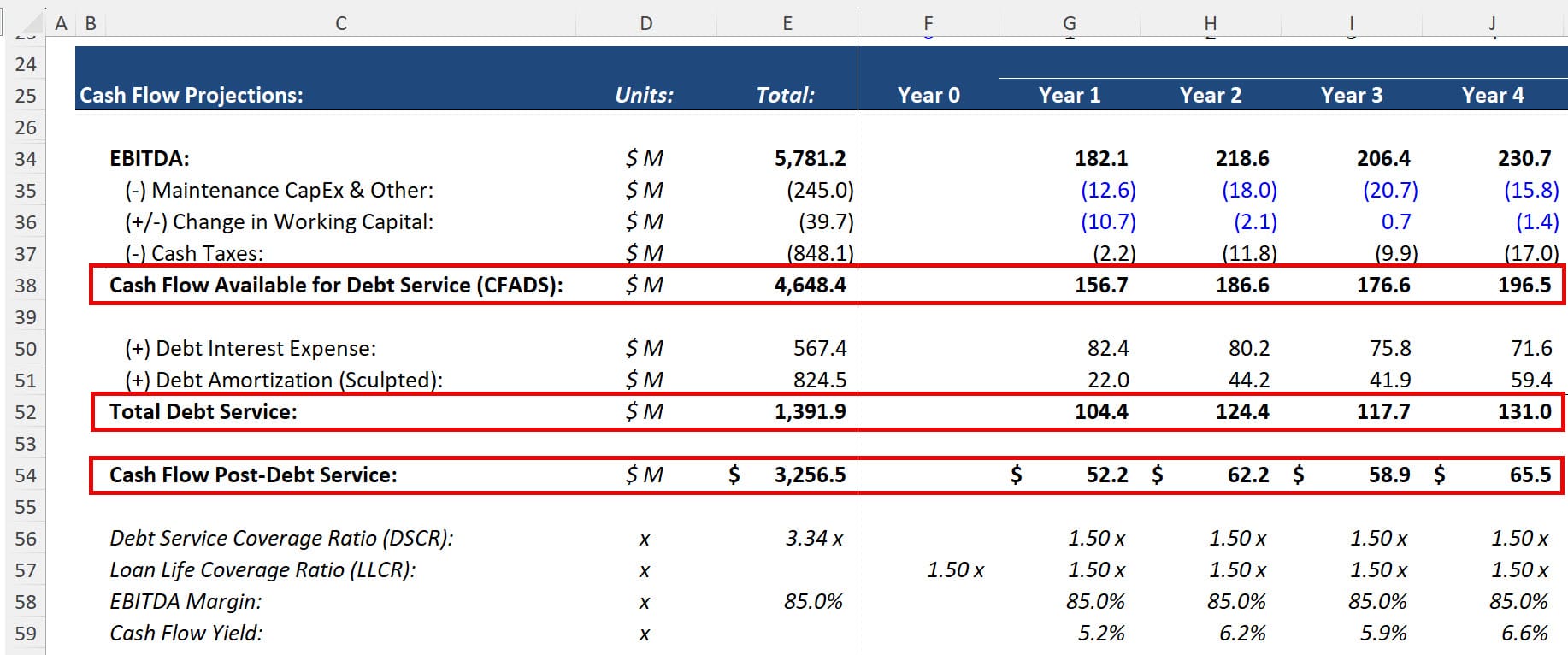

This is partially why they often require strict covenants linked to numbers like the Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR), defined as Cash Flow Available for Debt Service (CFADS) / Debt Service.

(Debt Service = Interest + Scheduled Principal Repayment; CFADS = EBITDA – Cash Taxes +/- Change in Working Capital – Maintenance CapEx +/- various Reserve line items.)

For example, a relatively safe asset, such as a power plant that sells electricity according to fixed rates and escalations, might be subject to a 1.50x minimum DSCR on the Debt used to fund the deal.

In other words, lenders want a 50% buffer to ensure the asset always has enough cash flow to pay them – and that’s for a “safe” asset!

In riskier verticals, such as mining, the required DSCR is much higher to account for the added risk of commodity prices.

Time Frame and Model Structure

The time frame and model structure also differ in Project Finance.

Since many of these assets last for decades, you could potentially set up a financial model that extends 20, 30, or even 50+ years into the future.

This would never happen in corporate finance because forecast periods rarely extend beyond 3 – 5 years.

The cash flows of normal companies are less predictable, so it’s rarely worthwhile to go far into the future.

Even if you create a far-in-the-future forecast for a tech startup that takes 20 years to reach maturity, the distant forecasts will become less detailed.

Technically, you can set up a 3-statement model for both corporate finance and Project Finance deals, but it’s far more common in corporate finance.

Normal companies have significant overhead and are so affected by timing differences in cash receipts/payments that it makes sense to track these items in detail on the Income Statement, Balance Sheet, and Cash Flow Statement.

For Project Finance, though, cash flow is king.

Yes, assets like toll roads, wind farms, and lithium mines have full financial statements, but you mostly care about the cash flow – the amount available for Debt Service and the amount remaining to distribute after Debt Service:

Building a full 3-statement model does not add much because most line items outside the PP&E, Debt, Equity, and Cash are small.

There are usually supporting schedules for the CapEx, Debt Service, Reserves, and other elements, but these are separate from the financial statements.

Debt Usage and Terminal Value

In a standard leveraged buyout model, the Debt funding is usually based on a multiple of EBITDA or a percentage of the Purchase Enterprise Value (i.e., the value of the target company’s core business operations in the deal).

Lenders lend based on a company’s recent and near-term performance, not what it might look like in 5 or 10 years.

And in the final period of an LBO model, you assume an Exit Value for the company, which is also based on an EBITDA multiple.

This Exit EBITDA Multiple is based on the company’s performance at that time, such as its growth rates, margins, and Return on Invested Capital (ROIC).

Outside of LBOs, this Exit Value or Terminal Value concept is widely used in other corporate finance analyses, such as the DCF model.

The assumption is that the company will continue to operate “forever,” or at least for many decades, even if it no longer grows substantially.

In Project Finance, the model setup and underlying assumptions are completely different.

First, while the Debt could be based on an EBITDA multiple, it is often sized and sculpted to match the asset’s future cash flows.

In other words, the initial Debt balance is linked to the Present Value of the asset’s cash flows over the Debt Tenor and the type of “coverage” or “buffer” the lenders want.

Here’s an example in the simple model:

Meanwhile, the Terminal Value or Exit Value may not exist for infrastructure assets because they have limited useful lives and cannot operate “forever.”

For example, energy assets such as solar plants, wind farms, and nuclear plants eventually wear down and stop producing energy in an economically feasible way.

And something like an oil/gas field or gold mine will eventually run out of economically feasible resources to extract.

Including a Terminal Value may still be reasonable in some contexts, such as if the asset lasts for 30 years and you plan to sell it in Year 10.

However, if you do that, the Exit Multiple should be lower than the Purchase Multiple to reflect the shorter useful life (and it should be linked to the estimated remaining cash flows).

Most Project Finance models assume the holding period equals the asset’s useful life, meaning the cash flows stop after ~20 – 30 years.

Wait, How Does Project Finance Math Work?

Reading this description, you might think:

“Wait a minute. How can infrastructure private equity firms earn acceptable IRRs if there is no exit value or the exit value is greatly reduced? That’s a critical part of any LBO model.”

It’s a 3-part answer:

- Expected returns are lower – They’re often in the high-single-digit-to-low-double-digit range (e.g., an equity IRR of 7% to 13%).

- There’s substantial leverage in each deal – It’s not unusual to use Debt for 50 – 60% (or even more) of the purchase price or development costs.

- High margins and cash-flow yields make the math work – Many infrastructure assets have EBITDA margins of 50 – 60% or higher, with cash-flow yields above 10%. At these levels, the equity IRR can also be above 10% without an exit if the holding period is long enough.

Point #3 is never true in corporate finance because ~99% of companies do not have margins or cash-flow yields in these ranges.

Therefore, leveraged buyouts of traditional companies depend on making the company more valuable, repaying Debt, and exiting for a higher value.

But Project Finance deals are more about paying the right upfront price, using the right amount of initial Debt, and not screwing up the asset’s mostly-predictable cash flows.

Project Finance vs Corporate Finance: Final Thoughts

With the hype over EVs, renewables, and the “energy transition,” Project Finance has become a hot field.

While there are some downsides, such as lower pay and more limited exit opportunities, I think it does have more growth potential than traditional IB/PE careers at this stage.

Even the private equity mega-funds agree about the need to move into new areas: Rather than doubling down on standard leveraged buyouts, they’ve been expanding into private credit, infrastructure, and other fields.

In a world of 5%+ interest rates, the traditional LBO might not be a grand slam anymore – but a power plant could always be a solid double or triple.

Want more?

You might be interested in Corporate Finance Jobs: Cozy Careers, But Bad “Plan B” Options or Project Finance Jobs: Leveraged Finance Meets Special Purpose Vehicles and Granular Modeling?.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews