The Collapse of Silicon Valley Bank: The Start of Great Financial Crisis 2.0?

If you are currently breathing oxygen, you’ve undoubtedly seen the stories about Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse over the past few days.

In 24 hours, it went from “We’re fine, but we took some losses and need additional capital” to “The FDIC is taking over, the government has guaranteed uninsured deposits, and there might be additional bank runs and a financial crisis or three.”

It’s the second-biggest bank failure in U.S. history and the largest bank to collapse since 2008.

In this “emergency article,” I’ll cover:

- Exactly what happened, including some points I haven’t seen mentioned elsewhere.

- Why bank regulations, including those passed after the 2008 financial crisis, failed to prevent this.

- Who deserves the blame.

- Whether the “bailout” is really a bailout (yes) and whether it’s justified (debatable).

- And the impact on the banking industry, venture capital, and startups.

How Does a $200 Billion Bank “Fail” in 24 Hours?

Silicon Valley Bank did not “fail” in 24 hours.

It’s more accurate to say that the bank was failing for months/years, but a series of catalysts made everyone realize the failure in 24 hours.

To explain this point, we need to step back and explain the business model of commercial banks.

Some sources describe it like this:

- The bank accepts deposits from customers and pays them interest.

- Then, the bank lends these funds to companies and individuals and charges interest on these loans.

But this is not how it works in the modern economy and financial system.

The order of operations looks more like this:

- The bank creates loans based on demand (customers that need to borrow).

- These loans create matching deposits on the L&E side of the bank’s Balance Sheet, and the bank then finds real deposits or other funding sources to back the loans.

In other words, banks’ lending activities are not constrained by their deposits.

Look at any financial model for a bank, and you’ll see that loans – not deposits – are the key top-line driver.

Banks’ lending activities are constrained by:

- Regulatory Capital – All banks must maintain a certain amount of common shareholders’ equity to absorb unexpected losses on loans and other assets. So, past a certain point, they need to issue or save up more equity if they want to issue more loans (I’m simplifying; there are dozens of ratios and requirements, but most relate to common equity – see our Bank Regulatory Capital tutorial for more).

- Reserve Ratio Requirements – In “normal times,” banks must keep a certain amount of cash on hand to fund possible deposit withdrawals. But the U.S. eliminated these requirements in March 2020, and they’re loose or nonexistent in many other countries, so banks are limited mostly by their regulatory capital.

Even though banks are not “constrained” by their deposits, they still manage to their deposits, and most target a specific loan-to-deposit ratio.

However, the ratios got completely skewed with Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) because it accepted far more deposits than it knew what to do with.

This happened to the entire banking system over the past few years due to the amount of money printing during covid, but it was particularly extreme for SVB.

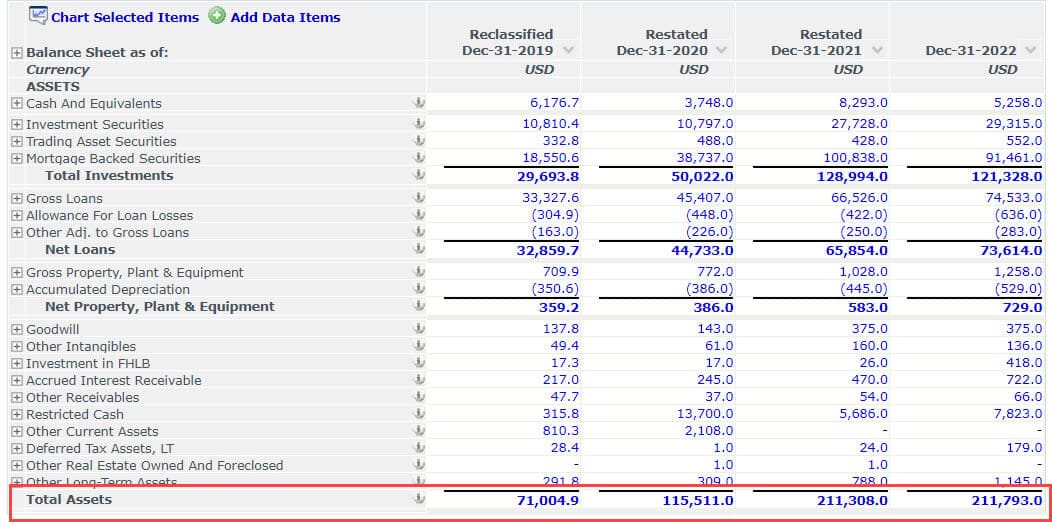

SVB’s deposits grew from ~$62 billion at the end of 2019 to $173 billion at the end of 2022, and its loan-to-deposit ratio went completely out of whack:

Tech startups were flush with cash due to a ridiculous fundraising environment in 2020 – 2021, and they put the money they raised in the bank.

Remember that, normally, a bank issues loans and then finds the liabilities (deposits, debt, etc.) to back them.

But the process went in reverse here: the bank got too many deposits and didn’t know what to do with the cash proceeds on the Assets side of its Balance Sheet.

They could have just left the funds in cash, but cash yielded ~0% in 2020 – 2021, so SVB put most of these funds in mortgage-backed securities and other U.S. government bonds:

In doing so, however, the bank and its “risk managers” made two key mistakes:

- Long-Term vs. Short-Term – Rather than putting these funds in shorter-term bonds that are less affected by interest rates, SVB invested mostly in longer-term, 10-year bonds whose prices drop significantly when interest rates rise.

- Insufficient/No Hedges – Rather than hedging their entire MBS portfolio with interest-rate swaps, the bank had… no swaps at all as of the end of 2022 (oh, and no Chief Risk Officer, either).

So, as the Fed hiked rates in 2022 into 2023, all these securities lost value.

But since they were classified as “Held to Maturity” (HTM) on the Balance Sheet, they were not marked to market value – so this loss in market value did not affect the company’s regulatory capital:

Not all the bank’s investments were in the HTM category; some were in the “Available for Sale” (AFS) category. These are marked to market value and do affect the bank’s common equity and regulatory capital ratios, such as its CET 1 Ratio.

This happens because Unrealized Gains and Losses on AFS securities appear within Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income.

SVB started selling these AFS securities to raise cash, and it revealed that it took a $1.8 billion loss on a $21 billion portfolio.

They needed to do this because depositors started withdrawing their money in larger numbers, and SVB did not have enough cash to meet the expected withdrawals.

But even without these withdrawals, the high burn rates for startups were another factor: too much spending and no new VC funding means “diminishing deposits.”

Immediately after this sale, the bank also announced plans to raise additional equity and convertible preferred stock.

These announcements caused panic among VCs and startups as they realized that the “stable bank” they relied on was not so stable.

The result was a modern bank run, as depositors attempted to withdraw $42 billion in deposits – almost 25% of the bank’s total – in a single day.

This left SVB with a negative cash balance, and the FDIC stepped in on Friday to take over.

Deposits up to $250K are insured in the U.S., but less than 10% of accounts at SVB were in that category (an unusually low percentage).

So, various “libertarian” VCs took to Twitter over the past few days to demand a bank bailout, arguing that there was a systemic risk and that the sky would fall unless the government stepped in.

On Sunday, the government did step in, with the FDIC, Treasury, and Federal Reserve guaranteeing uninsured deposits and creating a “Bank Term Funding Program” (BTFP) that will offer up to 1-year loans to banks that need it.

Wait, Shouldn’t Regulations Have Prevented the Silicon Valley Bank Failure?

If you’re familiar with bank accounting, valuation, and regulatory capital (i.e., from our Bank Modeling course), you might read the description above and have a simple question:

“OK, but what about the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR)? This ratio measures the bank’s liquid assets vs. its cash outflows in a ‘stressed’ 30-day period to ensure they can cover possible withdrawals.”

Yes, it does, and the LCR was created in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis specifically to prevent bank runs.

But there are two big issues with it:

1) Calculations – Banks have some discretion over what counts as a “high-quality liquid asset” (HQLA), and they rarely disclose the exact calculations. Also, the assumed “run-off rate” in deposits is discretionary, and you’ll often see numbers such as 10-20% – not the 25% that SVB experienced in a single day.

2) Applicability – In the U.S., the FDIC removed the full LCR requirements for banks with less than $250 billion in assets in 2019.

Conveniently, SVB stayed just under that $250 billion level in its past two fiscal years:

The other regulatory capital ratios and requirements, such as a minimum CET 1, would not have helped unless the bank had classified all its HTM securities as AFS, but there was no “requirement” to do that.

Finally, there is also the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR), but that focuses on longer-term funding, and many smaller U.S. banks are exempt from it.

As SVB so eloquently described these requirements in its filings:

Whose Fault Is the Silicon Valley Bank Collapse?

It was interesting to watch the usual suspects on Twitter – mostly wealthy VCs – blame “the government” for this failure while simultaneously demanding a bailout from the government.

The Federal Reserve does deserve some blame here because it kept interest rates at or near 0% for over a decade and then rapidly reversed course and raised rates quickly in a short period.

Also, regulators were asleep at the wheel and made bad decisions in exempting smaller banks from the LCR, NSFR, and other requirements.

But the root causes of the SVB failure were management’s incompetence and inability to manage risk, combined with the tendency of venture capitalists to act like crazed lemmings on sugar highs.

Yes, rapidly rising rates caused problems in many sectors, but Silicon Valley Bank could have managed the issue better in countless ways.

Here are just three ideas off the top of my head:

- Hedge with Interest-Rate Swaps – Yes, hedges cost money, but that’s the point: SVB already had too much cash from excess deposits, so why not buy enough swaps to hedge most of the MBS?

- Set Up a “Bond Ladder” – You know, just like every retail investor does. Buy a mix of short, mid, and long-term bonds rather than betting everything on long-term securities with much higher interest-rate risk.

- Leave the Proceeds in Cash Temporarily – Some banks, like Fifth Third, did this, with the CFO stating that the bank “could afford to be patient.”

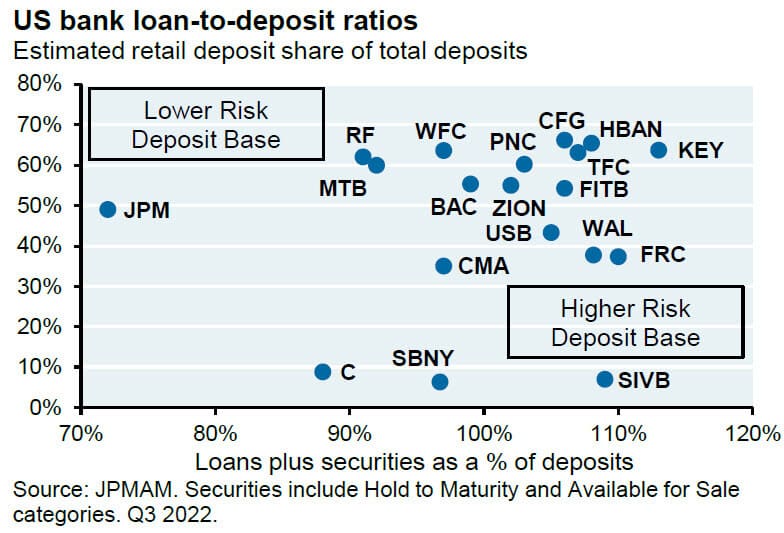

This great report from market strategist Michael Cembalest at JPM makes clear how much of an outlier SVB was:

The argument that “the Fed lied” about raising interest rates, so everything is the Fed’s fault, is ridiculous because it’s not the Fed’s job to provide investor guidance.

Hedging exists because anything could happen, and it’s the bank’s job to understand financial markets and why Treasuries are not, in fact, “risk-free.”

Venture capital firms also deserve some of the blame here.

First, they told all their portfolio companies to bank with SVB, creating a huge industry concentration risk:

Second, in the past week, VCs arguably engineered this run on the bank by panicking on social media and telling their portfolio companies to withdraw funds.

For an industry that supposedly funds “innovation” and “disruption,” VCs often act like a herd.

Is This “Bailout” Justified? Is It a Bailout? What Happens Next?

Despite what people like Bill Ackman and Jim Cramer are claiming, the government intervention to save SVB is, in fact, a bailout.

Shareholders and bondholders are being wiped out, so in that sense, it’s different from the 2008 bailouts.

However, the Fed is still offering to accept HTM bonds with significant unrealized losses at par value as collateral for short-term funding.

In other words, banks get to pretend their massive losses on bonds “do not exist.”

And the FDIC insurance fund will extend to all depositors at SVB and Signature Bank (another failure over the weekend).

The government says that this will “not be funded by the taxpayer,” but that’s deceptive because:

- Higher FDIC fees to pay for these programs will be passed onto the depositors at banks, most of whom are taxpayers.

- The Fed will almost certainly print more money to fund parts of this, creating more inflation – another tax.

In short, I don’t think this is a great idea, but it’s probably the “least bad” solution they could have come up with on short notice.

Banks are now incentivized to be even more reckless in their “risk management” since they know this backstop exists.

Why bother using hedges if the government will swoop in to save your failing bank whenever rates go up?

Why bother managing your regulatory capital if the government will save you when too many loans default?

Technically, the terms of this bailout limit the rescue to banks’ existing bonds and liquid assets.

But the problem is that it sets the precedent that the government will do this whenever there’s another similar issue.

The Impact on Investment Banking, Commercial Banking, Venture Capital, and Tech Startups

The good news is that nothing here affects investment banking in the U.S. substantially because the biggest banks (JPM, Citi, Wells Fargo, and BofA) are all perceived as “safe” and will benefit from deposits shifting from smaller banks to larger ones.

And the middle-market and boutique investment banks don’t have much presence in commercial lending anyway, so they’re not at risk of bank runs.

If anything, all this activity with asset sales and acquisitions will boost your prospects if you’re in a group like FIG.

But commercial banking is a different story.

The government’s actions over the weekend did not seem to reduce panic in the sector, with regional banks like Western Alliance Bancorp and First Republic down by huge percentages in pre-market trading on Monday.

There will probably be a mix of bailouts, acquisitions, and asset sales for these banks, and depositors will not lose anything due to government intervention.

But these actions set a negative precedent because they’ll encourage even higher concentration and even worse risk management.

It’s also clear that the regulations passed after the 2008 financial crisis have not worked as intended – or that their implementation was unsuccessful.

To me, the entire situation is: “The system wasn’t working, regulations were not implemented correctly, and we made some bad policy decisions – but rather than fixing the root problems, we’ll just apply a band-aid fix.”

The Fed is now stuck between a rock and an even harder hard place: if they increase rates or keep them higher to fight inflation, they get even more bank failures…

…and these bank failures, in turn, mean more money printing and/or higher bank fees to support more bailouts…

…which leads to higher inflation.

It’s a circular reference, but in real life rather than Excel.

I also expect blowback against tech startups and venture capital firms because of their close association with SVB and because bailouts are extremely unpopular.

Many banks will become even more skeptical of startups or impose onerous terms for simple checking/saving services.

Startups were already struggling in the current environment due to higher rates, a slowing economy, much tougher fundraising, and high-profile crypto failures like FTX – and SVB has only added to these troubles.

I expect hiring at VC-backed companies to fall even more, and VCs will struggle with more portfolio companies underperforming.

Even if you’re determined to work at a startup or win a VC-related job, you might want to re-assess your plans for the next 6-12 months.

In early January, I predicted that the markets in 2023 would be “Bad, but not as bad as 2022.”

Two months into the year, that prediction looks questionable.

But at least everyone will get their deposits, right?

—

If you liked this article, you might be interested in reading my analysis of UBS and Credit Suisse: The Next Shoe to Drop in the Financial Crisis of 2023?

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

What are your thoughts on the recent collapse and acquisition of Credit Suisse? Having been an investment bank, it seems like it would be particularly relevant to the readers of this blog (at least the ones in Europe).

https://mergersandinquisitions.com/ubs-and-credit-suisse/

Hey Bryan,

I think this is the beginning of the end of commercial banking as we know it.

These moves seem designed to further centralize banking, paving the way for a CBDC.

If everyone banks at the Fed, the government can better track citizens and their money, engage in highly targeted stimulus, and print unlimited money so bank runs are impossible…

You might be right; I don’t know, but I am hoping people have become a little more skeptical toward the government and “authorities” after the past few years. On the other hand, people also seem to be dumber than ever, so maybe that is just wishful thinking.

Good article. Thanks for summarizing everything. I guess my biggest issue with this is how many different stakeholders dropped the ball in all of this.

VCs- I dont expect start up companies to do a deep dive in the risk profile of their bank. But only having a bank account with one bank is insanity. Forget about banks failing, just think how often a bank has technical issues that shut down access. Any VCer should guide a portfolio company to open an account with a second bank. But beyond that, top VCers should have had a better understanding of the bank they were blindly leading customers. They work in a risky area as it is.

Regulators – people outside of the bank and regulatory bodies pointed out the problems with banks like SVB. Any regulator would have had far more data and a better understanding of the issue. The fact they did nothing, even with the latest banking regulations removed, shows how utterly useless they are.

Management – as you said, buying long term fixed assets all at the same time and around the same rate is crazy. Not hedging that risk is beyond crazy. They should be barred from working in financial services again. Too many people here manage to fail upwards.

The West’s biggest problem is how many people how gotten complaisant.

Yup, agreed. I think everyone just inhabits bubbles these days and never thinks much about what’s going on around them, whether it’s VCs, startups, the Fed, regulators, management teams, etc. I don’t know. It’s all very depressing, but I’m not sure what the solution is, or if a solution even exists. I’m much less optimistic than I was in 2010, 2015, or even 2020.

Great breakdown! Really appreciate these, I’ll be sending this along to others I know are curious.

Thanks!

What do you think happens with Leerink? A spin out?

Good question. Yes, probably a spin-off or divestiture, similar to what CS is doing with its IB division.

Any advice for those incoming at Leerink?

All you can really do is interview around and try to find something else as a backup plan. But I don’t know how well it will work right now since most firms are currently focused on summer internship hiring for next year. Also, you would only have a few months to find something else, and it normally takes longer than that.

Honestly, I would probably just wait until they tell you something or announce specific plans for Leerink. Banks still need to preserve their hiring practices and new hires even if they’re sold or spun off. Positions tend to disappear only if the bank completely collapses, but that seems quite unlikely here.