The Great SPAC Scam: Why SPACs Are a Great Deal for Celebrity Sponsors, But Not Companies or Normal Investors

Or you might have said that you agree or disagree with their political views.

But as of last year, there’s a new answer to this question: they all have SPACs, otherwise known as Special Purpose Acquisition Companies.

However, a more accurate abbreviation is “SCAMs” – since that’s what they are to most normal investors and normal companies.

In this article, I’ll break down the SPAC scam and explain why it’s yet another sign of a bubble ripe for a correction:

The SPAC Scam Explained

This article is based on a recent YouTube video on the same topic, which you can watch below:

Resources:

The video focuses on “SPAC models” in Excel, but in this article, I will spend more time on the process and mechanics.

Also, I will address some of the counter-arguments from SPAC supporters here.

The Short Explanation of SPACs

First, a “celebrity” or another notable person (the “Sponsor”) raises capital by taking an empty holding company (the SPAC) public in an IPO.

This SPAC then uses the cash proceeds from the IPO and a large stock issuance to acquire a private company, making it public.

Since the SPAC issues so much stock to do this deal, the private company ends up in control of the entire entity. As a result, it’s called a “reverse merger.”

SPACs are yet another alternative to the traditional IPO process and can be faster than IPOs.

Unlike IPOs, however, the Sponsor gets a 20% stake, called a “Promote,” and there’s much less regulatory scrutiny.

Oh, and this “Sponsor” invests almost nothing in exchange for this 20% stake.

As a result, the Sponsor could walk away with millions or tens of millions of dollars even if the SPAC performs horribly and the share price plummets, while normal investors will lose everything.

And even if the post-merger SPAC performs well, the Sponsor earns a disproportionate amount of the proceeds.

A SPAC with these terms is like a call option that has a payoff if the company’s share price increases above the exercise price and if the share price falls by almost 90%!

SPAC Mechanics, Part 1: The IPO

It’s best to think of SPACs in a 2-step process: the initial public offering (IPO) for the SPAC itself and its reverse merger with a private company.

In Step 1, the “Sponsor” forms a SPAC and purchases warrants to cover underwriting fees and other expenses associated with the IPO.

Then, this Sponsor gets a “Promote” for 20% of the company’s equity for a “nominal investment” (e.g., $25,000).

The SPAC then goes public and sells units, shares, and warrants to public investors.

The gross proceeds from the IPO are kept “in trust” until the SPAC finds a real company to acquire. If it does not find one within 18-24 months, it dissolves.

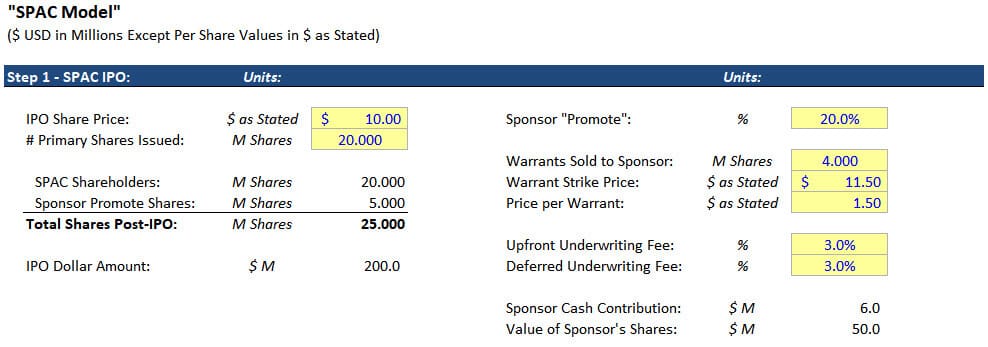

Here’s Step 1 in Excel:

SPAC Mechanics, Part 2: The Acquisition or “De-SPAC”

In Step 2 – the reverse merger – the SPAC identifies a target company and negotiates an acquisition where the target becomes the majority owner.

The SPAC shareholders get to “vote” on this deal, and if they don’t like it, they can redeem their shares… in theory.

If the deal is approved, the target company merges into the SPAC and becomes public, and the SPAC’s cash pays for the target’s equity, repays debt, or is kept on the Balance Sheet.

Also, another investor might put money into the post-merger SPAC via a private investment in public equity (PIPE), so its cash balance increases:

SPAC “Models” vs. IPO “Models”

SPAC “models” and IPO “models” are similar in that there isn’t much to model.

Only the company ownership and cash balance change, so you focus on those.

In a typical SPAC deal, the entity might raise $200 million by selling 20 million shares for $10.00 each in the IPO, and the Sponsor gets 20% as a “Promote.”

The Sponsor might also buy 3 – 5 million warrants for $1.00 – $1.50 per warrant at an $11.50 strike price.

These proceeds pay for the IPO underwriting fees, half of which are charged upfront in the IPO and half of which are deferred and charged upon completion of the reverse merger.

The total percentage is around 5-6%, which is slightly less than the standard 7% in IPOs.

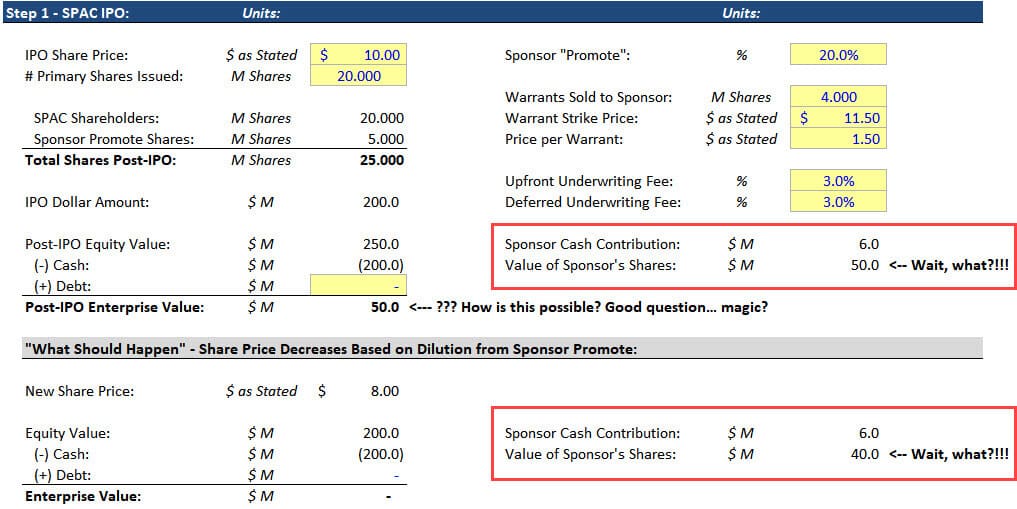

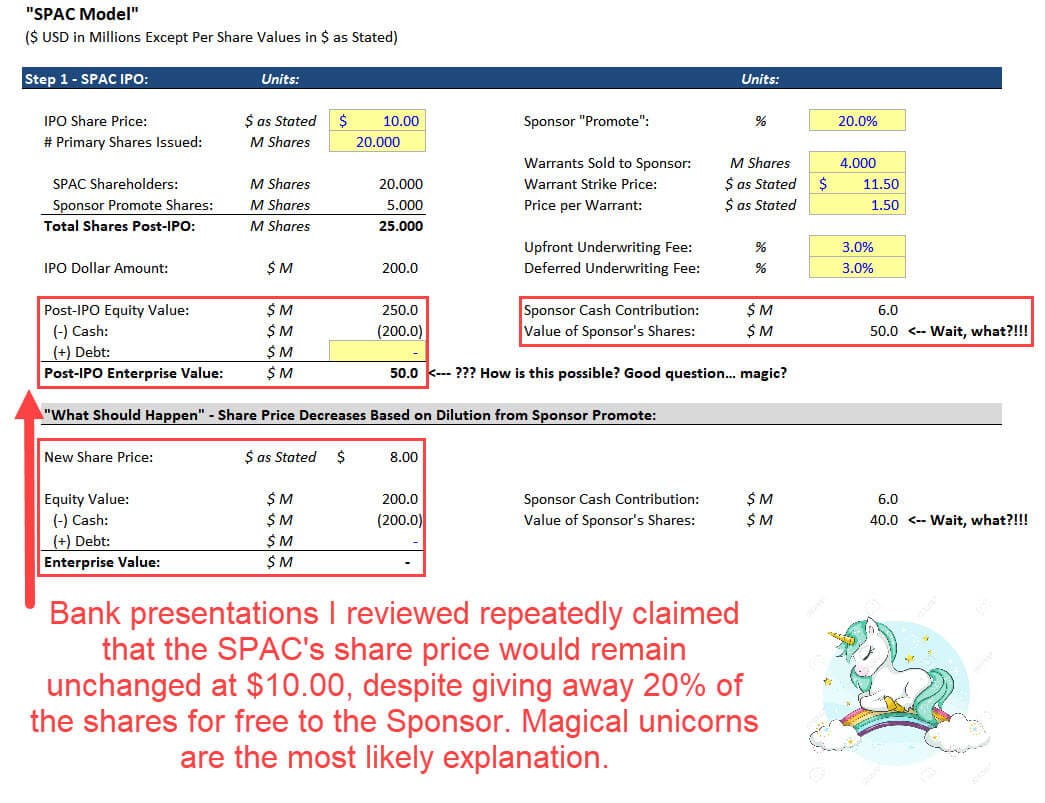

If you look at this first step in Excel, you can see part of the problem already:

Yes, that’s right: with these sample numbers, the Sponsor ends up owning shares worth $40 – $50 million despite paying only $6 million to purchase the warrants.

Also, if a company has no net operating assets, its Enterprise Value should be $0.

But if you assume that 20% of these shares are magically created and granted to the Sponsor – as the $10.00 share price stays the same – the Enterprise Value is not $0.

I believe the share price should decline to account for this dilution, as shown below:

But the bank presentations I found insisted that the initial $10.00 share price remains at $10.00 throughout the entire process.

If you have an explanation, feel free to leave it in the comments below.

SPAC Models, Part 2

When this SPAC finds a promising private company, it will attempt to negotiate and complete an acquisition.

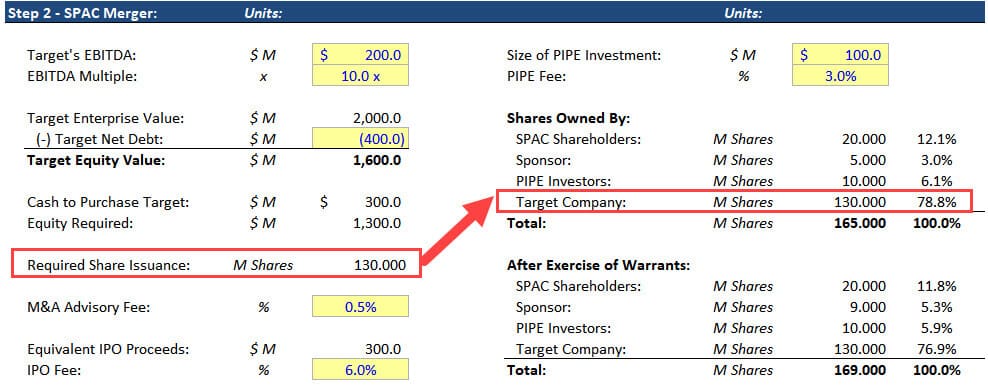

Let’s assume that it acquires this private company for a Purchase Enterprise Value of $2 billion and Purchase Equity Value of $1.6 billion, also recruiting other investors for a $100 million PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity).

In this scenario, the SPAC can use $300 million of cash to purchase the target, and it issues shares for the remaining $1.3 billion.

Because of the Sponsor and PIPE investors, though, the real company gets diluted more than in a traditional IPO.

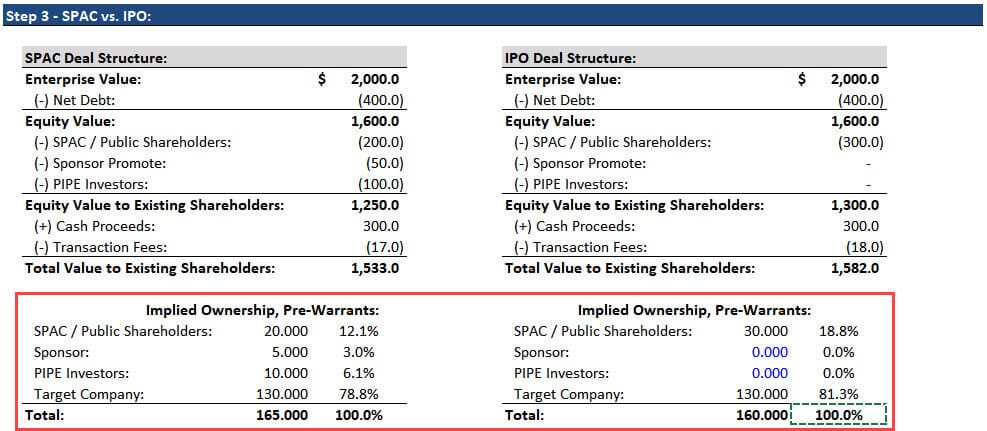

Here’s a direct comparison of the outcome from a SPAC vs. a traditional IPO with the same $300 million raise:

These numbers are before the Sponsor warrants as well – with those warrants included, the company would own ~77% rather than ~79%.

The bottom line is that in both a SPAC and an IPO, this company raises $300 million of cash and becomes a publicly traded entity.

However, it retains 2-4% more equity in an IPO, and its existing shareholders realize more value.

The total fees in a SPAC charged to the company are a bit lower, at 5-6% of the proceeds rather than 7%, but there are also more categories of fees, such as the ones for the reverse merger and PIPE.

Why SPACs Are a Racket

For Sponsors, SPACs are like call options with payoffs even if the company’s share price falls significantly.

Let’s continue with the numbers in the example above and say that you buy SPAC shares for $10.00 when it first goes public.

Then it announces a $2 billion acquisition, but once the acquisition is complete, the market doesn’t like it, and the share price falls to $5.00.

You’re now down 50%.

The Sponsor, meanwhile, still has a stake worth $25 million – all from an initial $6 million warrant purchase.

In other words, you assume the full downside risk when you buy into this SPAC, while the Sponsor loses nothing unless the share price falls by almost 90%.

But let’s say this acquisition goes well.

Maybe the SPAC announces the deal, the market likes it, and the share price increases to $20.00.

Great! You’re up 2x on your initial investment.

But now consider the Sponsor: its stake is now worth $100 million on an initial $6 million investment, which is a ~17x multiple.

So, the Sponsor benefits disproportionately when the SPAC’s share price increases, and it also has far more downside protection when its share price falls.

SPAC Performance So Far

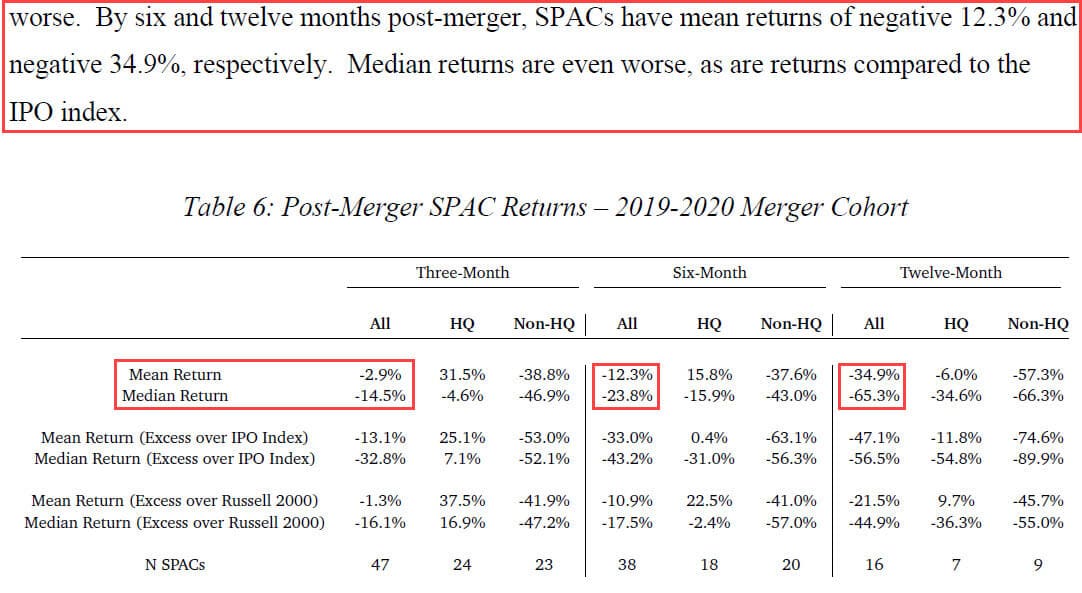

This survey of SPAC performance from this academic paper says it all:

SPACs launched in 2019 and 2020 have mean returns of negative 12.3% and negative 34.9% over 6 and 12 months, respectively, following merger announcements.

People often push back against these stats and point out that post-IPO share-price performance is also poor or questionable, depending on the time frame and region.

I agree that IPOs are often a bad deal for public investors, but there’s a big difference: transparency.

With an IPO, you know what you’re getting, and you have the company’s audited financial statements, risk factors, and existing shareholder information.

And no “Sponsor” is magically getting a percentage of the business in exchange for almost nothing.

Arguments in Favor of SPACs

I received some criticism on YouTube for presenting this view of SPACs without pointing to their supposed benefits.

The main arguments in favor of SPACs seem to be:

- SPACs cannot completely bypass the SEC, and they are still regulated once they acquire another company.

- SPACs are still faster and cheaper than traditional IPOs, so they offer some benefits to companies that need to go public quickly.

- The 20% Promote is not “free money” – it’s payment for the Sponsor, which has to do the work of finding a target and negotiating a deal.

- The Sponsor does not have access to the funds until the acquisition occurs, so it can’t just take the cash and run. Also, retail investors can sell their SPAC shares for $10.00 at any time before the deal takes place.

- Your example has numbers with misaligned incentives, but not all SPACs operate like that. It is possible to align the management team, investors, and sponsors.

And here are my responses:

Point #1 – SEC / Regulatory Scrutiny

Yes, once the SPAC has acquired a real company, it must file annual and quarterly reports, just like other public companies.

But it still skips the normal back-and-forth process with the SEC in an IPO or direct listing, and that’s where many changes are made.

And before the merger takes place, you’re still betting on an empty holding company with no track record.

Point #2 – SPAC Speed and Fees

Yes, it’s faster to go public via a SPAC.

The entire process might take 3-5 months rather than the 6-12 months required in an IPO.

As far as fees, we covered them above: yes, the percentage charged on the proceeds is lower (5.5% or 6.0% rather than 7.0%), but the PIPE and reverse merger fees increase the total.

But the real question is, are these benefits worth the disadvantages?

Is it worth paying 1.0% or 1.5% less in fees or going public a few months earlier in exchange for 2-4% of your company’s equity?

That’s an easy “no” from my perspective.

Point #3 – Is the 20% Promote “Free Money”?

The Sponsor spends time and money searching for acquisition targets, so it is doing some work.

But the question is: “Does the Sponsor’s work justify the 20% Promote and the fact that they will not lose money even if the SPAC’s share price falls by almost 90% following a deal?”

Again, my answer is no.

The Sponsor should contribute more capital, or it should share more of the downside risk.

Point #4 – Inability to Access the Cash Until the Acquisition

I agree that the Sponsor cannot “take the money and run” after launching a SPAC.

But the real risk is that the Sponsor could execute a terrible deal to do a deal, and even if the share price plummets, they could still make money (see above).

And yes, retail investors can sell their SPAC shares for $10.00 before any deal is announced.

But the risk is that they hold them until the acquisition is announced, and then the share price plummets because the market doesn’t like the deal.

That could happen with any company in any deal, of course – but “normal” deals do not have Sponsors that still come out ahead in this scenario.

Point #5 – Misaligned Incentives

Finally, yes, it is possible to use different deal terms and align the incentives by making the Sponsor pay more for the warrants or granting them a lower Promote.

But most SPAC deals are not currently structured like this, so I am focusing on what’s happening in the market – not what might happen or what should happen.

And yes, some companies that have gone public via SPACs have performed well.

Examples include DraftKings [DKNG], Butterfly Network [BFLY], Tattooed Chef [TTCF], and Virgin Galactic Holdings [SPCE].

But we’re talking about industry-wide percentages here, not a few deals that have done well.

And the performance data across dozens of SPACs over the past 1-2 years is quite poor.

What Would Change My Mind About SPACs

I’ll close this article by reminding you that I could be wrong about everything and that I have been wrong about plenty in the past year.

For example, I thought the S&P 500 would fall by far more than it did (1,000 – 1,500 range rather than ~2,200).

I also thought that banks might cancel internships, but canceled internships ended up being more common in other industries; banks just made them “virtual.”

That said, I feel more confident about my SPAC predictions than I do about the S&P, crypto prices, or bank internships.

I would change my mind about SPACs if one or more of the following points were true:

1) The Sponsors did not receive a “Founder Promote,” or they received a Promote only after the public investors earned a certain return.

For example, Bill Ackman’s SPAC, Pershing Square Tontine Holdings [PSTH], is one of the few exceptions that operates like this:

- There is no 20% Founder Promote.

- Pershing Square spent $67.8 million to purchase warrants representing a 6.21% diluted equity stake.

- And Pershing Square gets the 6.21% only if the public investors earn a 20% return first.

The Sponsor should not be able to walk away with tens of millions of dollars if the SPAC’s share price tanks after the reverse merger takes place.

If all SPACs used these terms, there would be a valid trade-off: the company can go public more quickly, but it’s not scrutinized as closely by regulators.

2) SPAC performance dramatically improved.

If the median SPAC somehow outperforms the S&P 500, the Russell 2000, the IPO index, or other key indices, I’ll accept that I was wrong and that these Sponsors were investment geniuses.

3) Sponsors invested in SPACs in proportion to their 20% ownership.

For example, if a $100 million SPAC launched by Celebrity X also required a $20 million investment from Celebrity X to receive 20% ownership, I would have no issues with SPACs.

To SPAC or De-SPAC

I’m not too optimistic about the points above, but we’ll see what happens over the next few years.

Until then, if you want to get rich with SPACs, you should be a celebrity – or at least have a large following on Instagram or OnlyFans.

If that’s not you, maybe you can “borrow” one of Shaq’s social media accounts for 24 hours so you can launch your own SPAC (you can also pretend to be 1-2 feet taller).

Risk on!

For Further Reading:

- SPAC vs IPO: Performance, Excel Model Differences, Trade-Offs, and Retail Investors

- The SPAC Sponsor Bonanza – Financial Times

- SPAC Magic Isn’t Free – Bloomberg

- A Sober Look at SPACs (Stanford Law and NYU Law)

- Summary of This Paper

- Hedge Fund Manager Warns the SPAC Fallout is Coming – Institutional Investor

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Brian

I wonder if i can pick your brain on two things;

1) Why is it that a deSPAC cannot use an S3 registration statement post despac for 12 months (?)

2) Why is a deSPAC unable to issue restricted shares under rule 144 ?

TIA

I am not a legal expert or capital markets lawyer, so I can’t comment on those, sorry. This site deals with finance and financial analysis, not the legal side of deals.

You missed a key reason why SPACs under perform — really reverse mergers in general. They are used because the company that wants to be public doesn’t have good enough numbers to go public on the merits of their current balance sheet. You are starting with a lemon that couldn’t pass the scrutiny required to undergo the traditional approach to going public.

That is true, but we covered this point in other SPAC coverage on this site:

https://mergersandinquisitions.com/spac-vs-ipo/

In the case with Sharecare, a company where I was an employee, your comments regarding SPACs rings true. I am not an educated investor, only an employee who received a decent amount of shares that were worth over 100k on day 1 of their going public. It’s been a year or so now since opening at $10 /share and they have ‘tanked’ as you put it probably due to the market not liking the deal. If I had known about the SPAC SCAMS prior to Sharecare going public, I’d have my 100k.. Right now I don’t think there’s enough in my account to tip the mailman for Christmas. Thanks for the article.

Sorry to hear that. We do try to warn people about scams and unscrupulous deals and other activities on this site, but it doesn’t always get circulated widely…

Why sorry for him? He spent zero penny for that virtual $100k warrant.

Sorry in the sense that he likely joined the company partially because of the expected value of these shares, which ended up being worthless. Sure, he didn’t “lose” anything directly, but he still may have made a bad employment decision because of this.

Hi, Brian.

Thanks for such useful article. I work in a shopping center firm in Mexico, which in 2020 was the first company in the country to go public through a SPAC, just in time to be our life jacket for covid. Since I was aware of the implications of our SPAC proccess, I thougth of his pitfalls and the moral risks involved. Fortunatelly, at this day, none of the investors nor sponsor had withdrawn, even with covid severe troubles.

Do you think SPAC malpractices in US will inherently be repeated in other markets like Mexico? Is the SEC turning a blind eye on that malpractices?

Kind regards,

I can’t really say because I haven’t followed SPACs in other markets/regions. But I think whenever you have an instrument that gives one set of investors a huge advantage over everyone else, there’s the potential for trouble. So this answer depends heavily on how SPACs are implemented elsewhere, and whether the same terms exist there.

Thanks for all this info Brian. Do you like SPACs better for retail investors if they were to wait till after the SPAC merged with a private company before they invested?

Discovered a company I liked as an investment target post-merge but wary because they went through the SPAC process.

Yes, I think post-merger SPACs are more reasonable. There is still some regulatory risk because the acquired companies haven’t gone through the typical IPO process. But at least post-merger, you know what you’re dealing with and are no longer making a speculative bet on a shell company that may or may not ever do something useful.

Thanks for such a comprehensive account of SPACs. Two controversial Israeli cyber-hacking/malware companies, Cellebrite and NSO Group are using, or plan to use SPACs to go public. They are extremely controversial and NSO in particular has had a checkered history both on the financial market and in terms of the damage its products cause.

Could you tell me if there would be any particular benefit to a company facing such negative scrutiny in using a Space rather than an IPO? Is there less regulatory scrutiny? Less bad publicity for a potential investor to have to withstand?

So, I can’t comment on those specific companies because I do not know them and have not followed their story. There is less scrutiny when a company goes public via a SPAC because the registration process is different, and investors who bought SPAC shares don’t necessarily know what they’re getting because SPACs are vague about their acquisition targets. This is why there are so many pending lawsuits and other legal action around SPACs currently.

Thanks Brian much appreciated, great read!

Thanks!

Brian – thanks for the great model and explanation on SPACs.

One quick question. The equity value waterfall in step three results in Equity Value to Existing Shareholders of $1.25 billion.

Question is – should the shareholders actually receive 125 million shares (vs. the 130 million shares in the example)? This approach would further dilute existing shareholders, but maintain an equity value of $1.6 billion in the Implied Ownership table.

Just a thought , as I was having a challenge understanding the additional $50 million of equity value (assuming $10 dollars per share) created in the SPAC scenario (165 million shares) vs. the IPO scenario (160 million shares).

No, I don’t think so, or at least that is not how banks are presenting this scenario. The additional shares are there in the SPAC scenario mostly because there are more investor groups involved. The Equity Value is actually higher in the IPO scenario.

Brian – Thanks for this great post. A couple of technical question on the sponsor economics: (1) were you able to confirm what happens to the share price once the Sponsor Promote Shares convert to common (i.e., in reality does the conversion drive down the price per share)?, and (2) shouldn’t the Sponsor Warrants convert to common based on Treasury Stock Method (i.e., net settled shares based on current common stock price and the warrant’s strike price, versus the outright 4.000 shares you’re reflecting in Step 2), and therefore be less dilutive?, and finally (3) shouldn’t Step 2 reflect the additional Public Warrants held by the SPAC Shareholders (and therefore they will be less diluted)?

1) No.

2) Yes, but the exercise price may be set to a very low level, so we ignored it (as did bank presentations… no idea if it was an oversight or intentional).

3) Potentially, yes, but the # of warrants owned by SPAC shareholders seems to vary a lot, and not every SPAC shareholder necessarily owns warrants.

Brian, thanks for the write up. One question, in your SPAC vs IPO comparison, should you not assume a 10%-20% IPO discount to the for the IPO scenario? So in my mind, is the accurate comparison not SPAC sponsor dilution vs IPO discount? A SPAC can agree a deal with a seller/target without the seller having to suffer that particular discount, however of course in exchange they suffer dilution from the sponsor promote. So i guess if you are a vendor and you think you can get your IPO away without any discount then you would not merge with a SPAC, but if you think for whatever reason your IPO would need to be heavily discounted then i guess you can do the math re sponsor dilution vs IPO discount. YOu think this is the right way to think about the two scenarios? Thanks!

That is a good point, as there usually is some type of IPO discount. But the bank presentations I found all seemed to skip this point, so I followed what they did (even though it doesn’t really make sense, along with various other parts of the “analysis”).

I think what makes it tricky, though, is that the IPO discount is a bit nebulous because no one knows exactly what “fair value” is before the company goes public. Banks set the share price and get surprised all the time. So… the discount could be close to 0, or it could be substantial, or it could even be a premium.

Whereas with SPACs, the dilution is guaranteed because of the Founder Promote.

I think, though, that even if SPACs have slightly higher dilution on average, that’s a minor issue next to the fact that the incentives are misaligned, which hurts shareholders who hold on until the merger announcement.

Hi Brian,

I know this is off-topic but I was wondering if you had any advice for someone in my situation.

I am currently in my final year of university (target, UK) and didn’t manage to get any IB or ER internships for the summer. I don’t have previous experience in finance and I realise I got into finance really late. I have a strategy consulting internship (small no-name firm) and an accounting/operations internship during high school, and retail experience but nothing else. My plan is really to just get any relevant experience for the summer.

I am currently cold emailing boutique firms for potential internships in IB or private equity/hedge funds/asset management. I was wondering if my cold emails should specifically mention that I’m interested in interning at the firm or if they should be requests for informational interviews, during which I should then pitch for an internship. I could also attach a stock pitch for the hedge funds/AM firms but I’m not sure if this is a good idea.

Thanks for all the work you’ve put into M&I- really appreciate it!

I would directly ask about internships. You can potentially attach a stock pitch, but make sure it is very good first or it will hurt you more than help you. You should follow the set of steps described in this interview:

https://mergersandinquisitions.com/private-equity-internship-to-investment-banking-networking/

Why is your focus solely on holding through merger?

It’s well known in SPAC trading communities that most SPACs fall between DA and merger.

Buy at NAV, sell after it spikes on rumour or DA.

If we look at the most high profile SPAC as an example, CCIV, NAV was $10, it peaked at over $65 on rumour and spent 2 days at $30-45 after DA before falling further. Even now it’s still over 100% up from NAV.

Why is there an obsession on holding through merger? I leveraged my trades and made 240% on GIK, 80% on DPCM, 300% on FTOC and over 1000% on CCIV and personally I don’t care how much Klein or Cohen pocketed from the deal. Why is that relevant to me?

Invest near NAV, buy the rumour, sell the news. It’s an age old formula and it works for SPACs. Stop holding through merger and complaining that sponsors are making more money than you.

Why? Because that is the purpose of SPACs (in theory): they claim to be taking high-quality companies public so normal people can invest in them and earn something as the companies grow.

What you’re describing is gambling or “speculative trading.” There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s yet another sign of a bubble when people make more money speculating on shell companies than they do by investing in high-quality businesses.

I’ll enjoy watching the entire market crash.

Thanks Brian,

that’s a great overview! I’d also add $SKLZ to the list of the successful/ fair SPACs – the sponsors there are locked in for 2 years (vs 3months in the other SPACS), plus the company is a legit one and with track record. Btw, sponsors are the same folks who took $DKNG public. Maybe you’ve looked at $SKLZ – if so, would love to hear your views and whether I’m missing something.

Many thanks!

I have heard about it but not looked into it in-depth. I’m sure some legitimate companies have gone public this way, and SKLZ may be one of them. It’s sort of like the dot-com boom – a few legitimate companies/sponsors will emerge, but most of these entities will go nowhere or produce poor results because they overpay or can’t find the right company.

Brian, I will argue that from the sponsor perspective, one of the biggest reasons why VC/PEs are piling into sponsoring SPACs these days is because they can control the size of their ticket in a company where they have a high conviction of, if they decide to act as a backstop investor to the merger. Unlike in a traditional IPO where the book is controlled by the underwriter, the sponsor gets to control their own book, underwriting their own deals and not paying the 7% underwriting fee while reaping all the upside from the promote shares for their LPs. You will see a lot of these types of SPACs especially in the biotech world where the interests are highly aligned. SPACs are a mixed bag these days.

From investing perspective, for retail investors, SPACs can be treated as a convertible bond like instrument with great asymmetric risk/reward if they can get to buy it as close to $10 per unit as possible, on or shortly after the day of IPO, and then split the units once the derivatives underlying the units begin to trade separately. Investors can choose to redeem/sell the common and keep the warrant for the upside. It’s literally like a lottery ticket. Of course one cannot be fomo with this strategy and trying to hop on the hype train after a deal is announced. I’d buy SPAC units all day these days when the market tanks. In fact, I’d go as far as putting my emergency fund into the SPACs as close to $10 as possible. They are great cash like instruments unless the trusts behind SPACs collapse…which is highly unlikely.

Thanks for adding that. I guess I just don’t see it that way because the key risk is what happens after the merger takes place. Sure, before a deal is announced, the share price should not fall below $10.00. But afterward, anything can happen. Otherwise, why would SPAC performance over the past several years be so poor?

It’s true that the same can happen with normal stocks and M&A deals there as well, but there’s no “Sponsor” there who captures incredible upside with almost no downside risk… while offloading that risk onto smaller shareholders.